Introduction

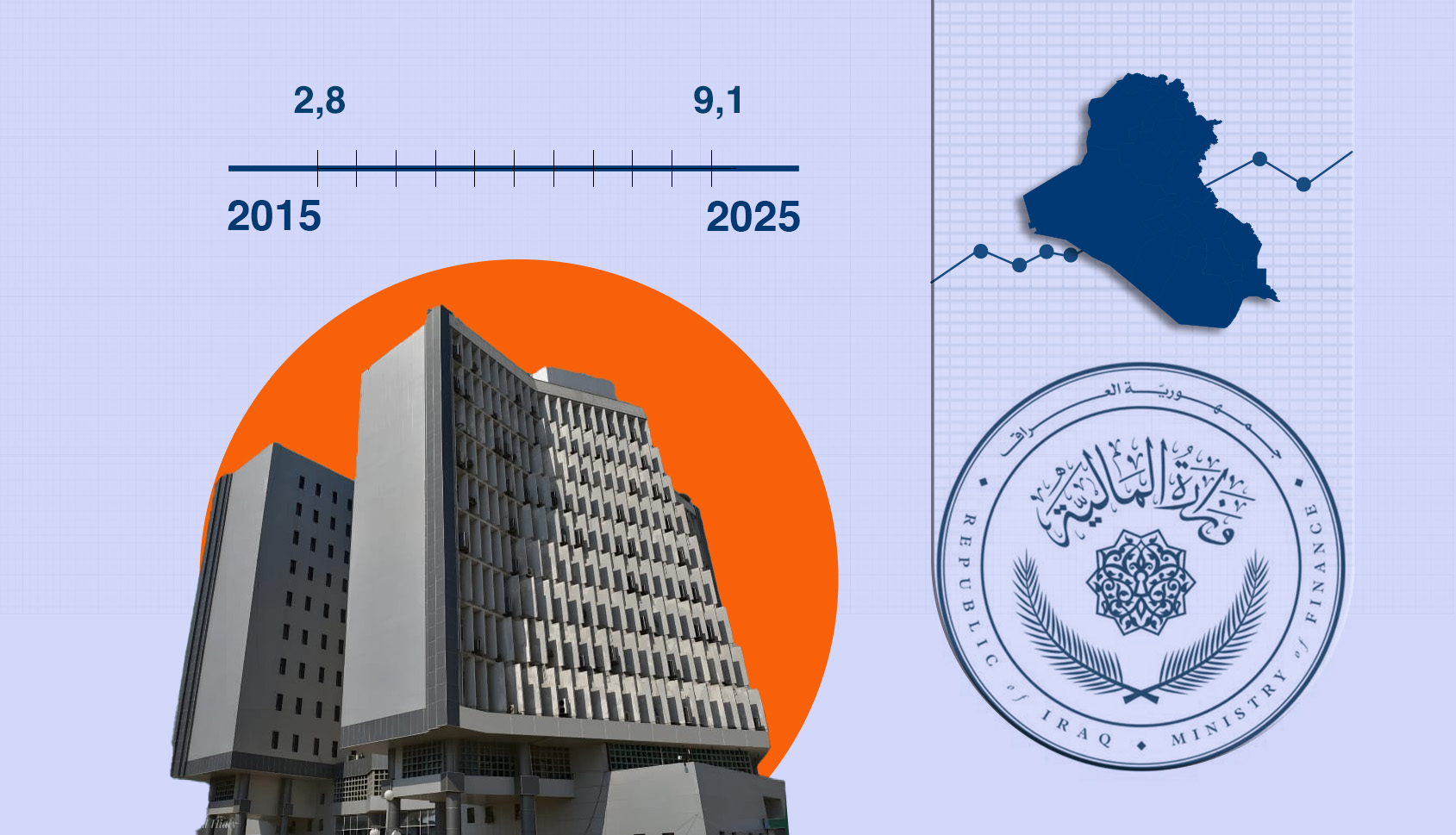

The recent remarks of Hayan Abdul Ghani, the Iraqi Oil Minister, regarding the oil and gas circumstances in the Kurdistan Region are noteworthy. These comments shed light on Iraq's proposed strategy for the future of the region's oil and gas industry. After ceasing oil exports to international markets for a period of two months and 15 days, the KRG experienced losses exceeding $2 billion. This calculation excludes the amount produced for local refineries. Oil production at the Sarqla, Khormala, Sarsang, Atrush, and other fields persisted at varying rates to fulfill local consumption needs in the Kurdistan Region. The question that emerges is how Iraq plans to approach the future of the oil and gas sector in the Kurdistan Region.

In this analysis, we'll dissect the Oil Minister's exclusive statements to the Rudaw Media Network from four perspectives, each highlighting Iraq's policy towards the oil industry in the Kurdistan Region and the Kurdish territories outside the control of the Kurdistan Region. These viewpoints encompass Turkey's denial to export oil from the Kurdistan Region and Kirkuk, Iraq's plan to review the oil contracts between the KRG and various oil companies prior to exporting oil, and the designation of oil and gas fields in Kurdish areas outside the control of the KRG or disputed territories as conflict-free zones.

Why is Turkey Hesitant to Export Oil from Kurdistan Region and Kirkuk?

The answer to this query seems apparent, particularly given the ruling of the ICC. Turkey is mandated to halt oil exports without the approval of SOMO (State Organization for Marketing of Oil), and it is obligated to pay $1.4 billion in compensation to Iraq.

The Oil Minister indicated that Turkey's decision to continue suspending oil exports from the Kurdistan Region and Kirkuk is not connected to purported technical problems with oil pipelines that followed the earthquake on February 6, 2023. There was a 47-day interval between the earthquake and the suspension, with oil exports being withheld for an additional two and a half months, four months post-earthquake. For 42 days, no problems surfaced, and Turkey has not completed pipeline inspections in over two and a half months. Evidently, the problem is not technical in nature, but rather rooted in other contributing factors.

The Minister of Oil in Iraq has stated unequivocally that Turkey has not sought a waiver for the $1.4 billion, and that Iraq has put the complaint for the years 2018 to 2023 on hold. Yet, the intentions of Turkey remain uncertain following the signing of contracts by SOMO to re-export oil from Kurdistan through Ceyhan Port. Answers to these questions are awaited in the coming days, especially during the second half of this month, when the production and export of oil from all fields in the Kurdistan Region are slated to resume.

A critical question that needs addressing is whether Baghdad, particularly the Shiite Coordination Framework, has withdrawn its support for the agreement between Erbil and Baghdad concerning the oil of the Kurdistan Region, same as what happened with Iraq's 2023 budget. Is it probable that the KRG might turn to Turkey to export oil beyond the measures mutually agreed upon by Erbil and Baghdad on April 4, 2023, similar to what transpired in 2014? Considering the possibility that Baghdad may not honor the agreements, the necessity for a new agreement is currently a point of debate.

Revisiting Kurdistan's Global Oil Deals

The forerunner to oil contracts in the Kurdistan Region is Production Sharing Agreements (PSA), a model that Iraq has historically dismissed. Even though Iraq has adopted this method in the fifth and sixth rounds of contracts for oil and gas exploration and development, set to be declared later this month, the Oil Minister described it as "profit-sharing, not production-sharing."

This distinction exists due to the presence of companies controlled by the Iraqi state and the Ministry of Oil, such as the Basra Oil Company and the North Oil Company. However, such state-owned enterprises are not present in the Kurdistan Region to participate in production, as outlined by the Oil Minister.

Furthermore, it is apparent that Iraq's demands conflict with those of international oil companies operating in the Kurdistan Region which insists on adhering strictly to their contractual terms, particularly the form of these contracts, without altering the distribution of production profits. At present, an Iraqi committee is scrutinizing these contracts, and a joint committee between the Iraqi Ministry of Oil and the Ministry of Natural Resources has been formed to review them.

In fact, the agreements between the Kurdistan Region and international oil companies extend beyond comprehensive production sharing contracts. They encompass oil extraction, drilling of new wells, development of oil fields, and even the management of exports and oil pricing based on the quantity and quality of oil.

Regrettably, the lobbying efforts of oil companies both within their home countries and through decision-making centers in Iraq to safeguard the contents of their contracts with the Kurdistan Region have yet to prove successful.

Despite the announcement of a joint venture on February 27, their operations have ceased, staff levels have been reduced to a minimum, and investment spending has been drastically cut. Resumption of exports, should it occur, will not entail further oil well drilling.

Presently, the joint committees are examining the contracts, while oil companies appear to be teetering on the edge of bankruptcy due to the cessation of their operations, ongoing costs, and expense reductions to the bare minimum. But will the review demanded by Baghdad affect these companies and the Kurdistan Region?

After all, these firms have invested in oil fields starting from scratch, some having expended millions of dollars without seeing any production. Iraq itself allocates over a billion dollars to field exploration and development in this year's budget alone!

The Iraqi Oil Minister's comments about the disputed areas warrant attention. He speaks with certainty regarding gas and oil contracts in the fifth round of Iraqi Oil Ministry contracts. Additional contracts are slated for issuance in the sixth round, with no participation from the Kurdistan Region. He contends these are no longer zones of conflict. However, according to Article 140 of the constitution, these areas are deemed contentious, with numerous Iraqi parliamentary and ministerial sessions failing to resolve the issue, despite the formation of committees across all ministries.

Could the Oil Minister Face Federal Court for Article 140 Violation?

The progress achieved by the Iraqi authorities in these areas stems from the internal divisions and weaknesses within the Kurdistan Region. If two decades of pragmatic steps have failed to implement a constitutional article, can this issue be resolved in a mere four years of government through the amendment of a law and the establishment of a committee?

The statement by the Interior Minister about purchasing oil from the Kurdistan Region for the domestic market raises several straightforward questions. How much oil will Iraq purchase from the Kurdistan Region for the domestic market? Will it be at the price as set in Iraq's 2023 budget or SOMO’s exportation price?

Indeed, conjecturing about the motives of Iraq's Oil Minister regarding oil production in the Kurdistan Region for anything other than preventing the collapse of the oil sector would be unfeasible. The Minister has explicitly stated that Iraq's potential to ramp up oil production in its fields could exceed a million barrels, barring any limitations set by OPEC. It then begs the question, why would Iraq purchase oil from the Kurdistan Region? It is evident that neither Iraq nor the Kurdistan Region possesses the refining capacity for such a substantial volume of oil. As such, any progress on this front could substantially jeopardize the Kurdistan Region's oil industry. While it is necessary to acknowledge internal conflicts, the balance no longer leans in Iraq's favor, as it did in the early days of ceasing oil production.

Another key consideration is the issue of oil pricing, specifically when the oil from the Kurdistan Region is destined for local consumption and directed towards local refineries. What would be the cost implications? Would it reflect the export price or the refinery price? If the latter, then according to Deloitte's 2022 report, the oil price discrepancy in the Kurdistan Region appears to have doubled. In such a scenario, who would shoulder this differential?

The Iraqi Oil Minister maintains that negotiations are progressing favorably, but if the Kurdistan Region's 400,000 barrels of production are allocated to Iraq, how will the budget shortfall be managed? Will Iraq handle the Kurdistan Region's budget share in a similar manner?

Conclusion

In nearly two decades, the Kurdistan Region's oil industry has been eclipsed by that of the Kurdish areas outside the Region. Even as the Oil Minister fails to acknowledge developments in the plains of Diyala, Kirkuk, and Nineveh as contested territories—a constitutional violation—Shiite representatives insist that other fields, such as Khurmala, and the Kurdistan Region should yield more than 400,000 barrels of oil. This is in the wake of amendments to Articles 13 and 14 of the draft budget law suggested by the Finance Committee.

These elements do not correspond. Roughly half of the Kurdistan Region's oil is derived from the Khurmala field, which Shiite politicians consider as part of Iraq's administrative territory. So how could the Kurdistan Region deliver 400,000 barrels to SOMO? Hence, all indications are disconcerting. Succinctly, if the Shiites rescind the agreement made on April 4, the negotiations may prolong and reaching a consensus could become unattainable, potentially leading to the reinstatement of previous management approaches!

Decisions concerning oil export or production in the Kurdistan Region may be reached in the upcoming days, particularly around mid-month, along with the responses of the newly established national companies to the contract review process.

Notably, when international companies initially invested in this sector, there was a dearth of information about oil fields and squares in the Kurdistan Region, including their economic viability. However, how will the data from these fields be handled now that it has been made available?

Had past Iraqi governments conducted two-dimensional seismic surveys or other types of oil and gas explorations in the Kurdistan Region, and allocated funds for these activities akin to the fifth and sixth rounds of contracts for other Iraqi fields, the contracts of the Kurdistan Region would be dramatically different today.