Summery

In this analysis, I revisit a short piece written by a well-known Kurdish expert on the transformative impact of Kurdistan energy, particularly following the KRG-Turkey agreement in 2013. I will try to use the piece as a premise to reflect on a timely and strategic area for Kurdistan and the region. The relationship between energy, Kurdish statues, and relationships with others. Doing that through demonstrating the piece's various problematic areas First of all, oil may be a less transformative factor than gas. Furthermore, relying on Turkey may not produce the desired results. At the time when Prof. Stansfield wrote his article, Turkey was enjoying his short-lived "trading state" era, but no longer after it went back to the dominant mode of a militaristic state. More importantly, as the analysis stresses, despite many political events over the course of a decade, Kurdistan's energy case proved to be multidimensional and far more complex.

Background

For Kurds, oil, and later, gas, have always been more than just energy or economic sources. Oil was discovered in Kurdistan for the first time in 1904[1] in a remote border area between the two dominant empires, the Ottomans and the Safavids. The Kurds and oil have a long, complicated, and mythical relationship. It entails empires, global superpowers, and a slew of multinational corporations[2]. Because of this long history, the Kurds consider oil to be the primary tool for creating and destroying powers and entities.

This formula serves as the foundation for a short piece written by professor Gareth Stansfield in 2014. Gareth was one of the names who worked closely and extensively on the Kurdish issue in Iraq after 1991. His writings are often painted with an optimistic view. His piece was titled: The Transformational Effects of the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq's Oil and Gas Strategy. It was published in Sciencespo: Centre de Recherches Internationales[3]. The following was the piece's main point:

- [Kurds] have rarely engaged in actions and activities that may be considered to be "transformational" in terms of how they would impact upon the broader milieu of Middle Eastern political and economic life.

- However, it is possible that this inconsequentiality may be resigned to the historical record as developments of potentially great consequence unfold in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

- The transnational effects of the growing oil and gas sector in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq are set to become significant following the signing of an agreement between Ankara and Erbil in November 2013.

The effect will have an impact on "not only the modes of state operations but also the very integrity of the post-World War I state system." After nearly a decade of the KRG-Turkey agreement and Gareth's perspective, we try to revisit this vision and ask whether oil and gas (energy) can change the status of Kurds, particularly in the Kurdistan Regional Government and the wider region. What were Gareth's anticipated challenges, and have they been met or have they changed? Is the local, national, regional, and international environment more or less favorable to such a change, or vice versa? Gareth based his assessment on the KRG-Turkey treaty[4], which was signed in early November 2013 and is known locally as the 50-year agreement.

For Gareth, the deal "has introduced a new and potentially transformative factor into how Ankara now views the emergent Kurdistan Region in Iraq. This is the combination of Turkey’s energy deficiency and the Kurdistan Region’s preponderance of hydrocarbons reserves." When Garth writes in his piece, Turkey was singling "to the Kurds that he supported KRG independence under the right circumstances"[5]. But in the fall of 2014, Ankara signaled to Erbil that Turkey would not support a Kurdish bid for independence.

What has changed?

In nearly a decade, two major political events occurred: the rise and fall of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the 2017 referendum. We consider the two events to be political events[6]. The latter refers to a moment and event that alters the conceptual and physical fabric of connectivity, relationships, pathways, and institutions. The two political events forced Kurdistan's ruling elites to change their ways. They can be classified as counter-events in many ways. While the ISIS war was intended to weaken, if not destroy, the Kurds, it instead empowered them. The referendum, on the other hand, which was supposed to empower the Kurds, did not turn out according to the Kurds' wish.

The two political events have a direct impact on the KRG's status and potential transformation. As a result, the KRG transformation is more than just having or building an energy sector; it is a multifaceted process. Events are shaping it more than anything else.

The international coalition's relationship with the KRG was renewed by the ISIS war, laying the groundwork for a possible long-term relationship based on security and civil-military cooperation. A modern army is required for Kurdistan to have any significance or undergo any real transformation. As a result, we can argue that the ISIS war aided the transformation process. To summarize, the ISIS war transformed Kurds into local partners, whereas previously they were more vulnerable tools used for geopolitical chess games, as Henry Kissinger outlines in a 1973 memorandum. [7]

During the war, the Kurds benefited from modern army building techniques such as training, leadership, and doctrine.

In contrast, the referendum backfired. If Gareth expected Turkey's attitude toward Kurds to change as a result of the energy deal, the referendum proved him wrong. "The referendum produced a rare convergence between Turkey and its regional rival Iran, as the two countries coordinated their support for Baghdad's tough response[8]."

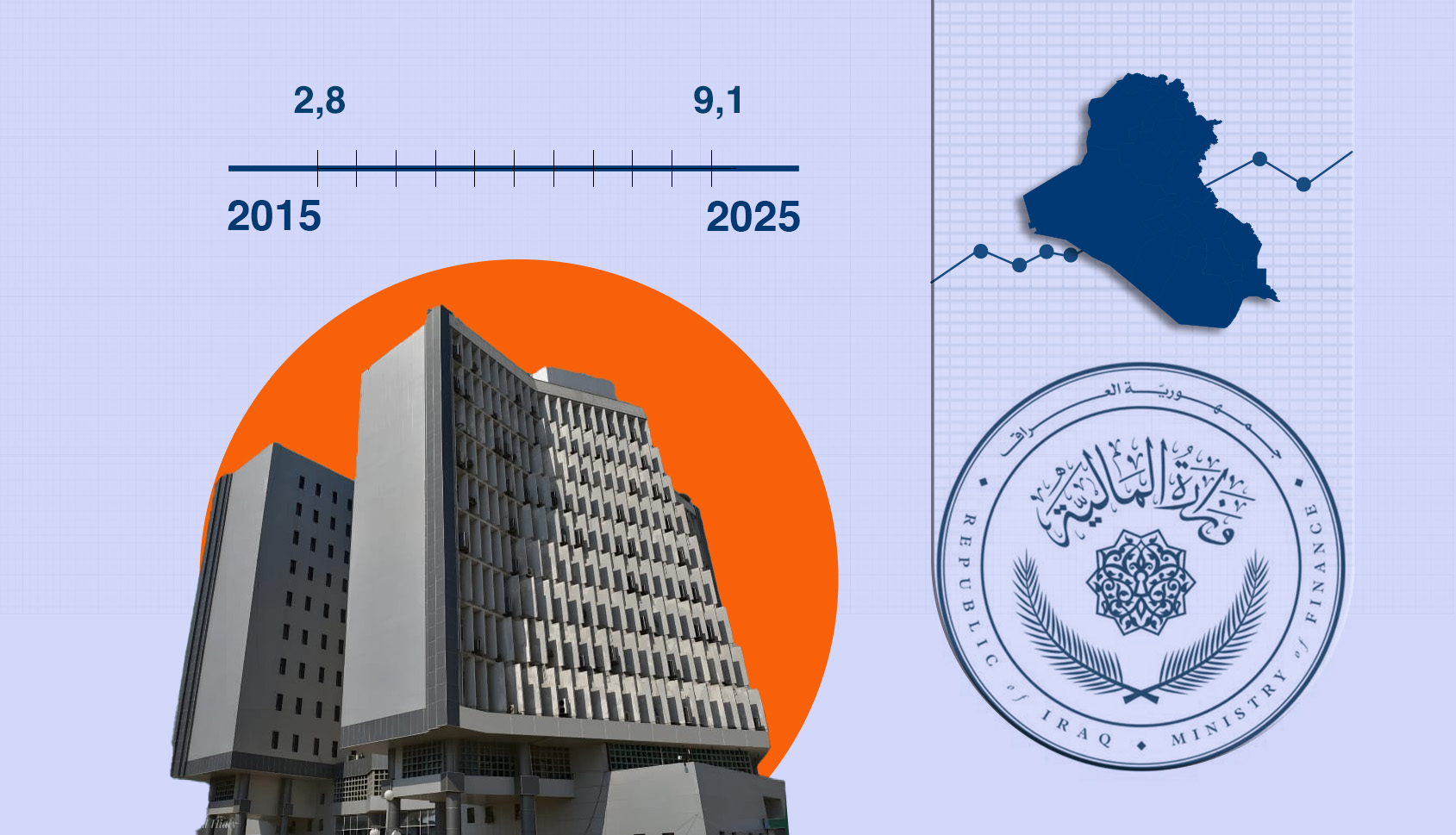

The KRG's main asset until the referendum was oil. The oil resources were dedicated to achieving independence[9]. The post-referendum period is notable for two reasons: less emphasis on independence and the emergence of gas as a transformative alternative to oil.

Welcome to The Age of Gas

Natural gas has emerged as a significant source of energy in recent decades. "Some of the most dramatic energy developments in recent years have been in the realm of natural gas," according to the Baker Institution[10]. The expansion of LNG trade has also aided in the development of a new, increasingly global gas market. It has transformed gas, which was previously a localized and difficult-to-transport resource, into a more liquid global commodity. Events such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have brought energy geopolitics to the forefront, complicating the landscape even further. The EU is seeking diversification, and Russia is no longer a reliable partner. Kurdistan has suggested that it "possesses the energy capacity to assist Europe." [11]

I contend that gas is more important in terms of any genuine change in the Kurds' and KRG's roles in the region. The pipeline infrastructure is extremely expensive to construct and necessitates long time horizons. These time and cost characteristics result in the emergence of a situation in which the connected countries must maintain good relations with one another. They also must devote significant political attention to ensuring the security of gas supplies. The pipelines will combine long-term relationships with economic and security policy. Gareth could only imagine gas at the time he wrote his piece, albeit optimistically.

However, for Kurdistan gas to become a game changer in the Middle East's Kurdish issue, it must rely on Turkey. The Kurds do not want this reliance, as demonstrated by the last decade.Turkey may have the intention of purchasing Kurdish gas, but in terms of geopolitics and domestic politics, it is no longer a trading state[12], as was once assumed. Unlike military or other forms of state, the trading state "enables a broader range of actors to participate in foreign policy-making or diplomatic games, and their interests and priorities are quite different from those of traditional Turkish foreign policy-makers." As a result, peace with neighboring countries will be critical. When Turkey was on the path of becoming a trading state, it aspired to have zero problems[13] with the neighbors. Rosecrance[14] emphasized in his book The Rise of the Virtual State how, in an ever-trading world, resolving disputes with neighbors becomes critical in terms of promoting trade and investment. This has all turned out to be a mirage, or at the very least, a short-lived policy.

This renders the entire Gareth approach unrealistic, at least for the time being and for the foreseeable future. It demonstrated that Kurdistan's energy, particularly gas, requires a confluence of factors to deliver. There are rivals and opponents. Take, for example, Russia and Iran. These two countries, particularly Iran, are opposed to the development of Kurdistan gas for two reasons: economic and geopolitical. Iran views KRG gas as a competitor in the Iraqi market.

For more strategic reasons, Iran opposes any Kurdish empowerment for domestic and regional reasons. Iran added another layer to this by connecting KRG gas to the United States and Israel. The KRG elites must try to cool relations with Iran.

One obvious point is that, despite its importance, Kurdistan cannot rely solely on Turkey. This also applies to any other player. With the shift in global politics, this is becoming more complicated. Energy has been and will continue to be central to the conversation. Energy is becoming increasingly important and in demand. This puts Kurdistan on the spot while also drawing unwanted attention.

The US is a supporter of Kurdistan gas [15].This is evident in terms of funding, support, and attitudes. Domestic dimensions, in addition to regional and international dimensions, may be more important.

Conclusions

Energy has been at the heart of unmaking the Kurds in Iraq. Will that trend be turned around after the Kurdish ownership of the resources? More than just energy is required for energy to become a transformative tool: proper policy, domestic harmony, and societal support.

Oil and natural gas can be found in Iraqi Kurdistan. These resources are more than just energy sources. Kurdistan's energy history can be divided into two periods: oil and gas. With the independence wars, the oil political era came to an end. Hence, gas developed into a very different history. Can gas become the source of connectivity? The development of the gas sector is seen by regional powers as part of the KRG's empowerment. Gas is more valuable geopolitically than oil. At any time, the oil relationship could be terminated or transferred in more than one way. In contrast, gas is expensive to transport and export. Long-term gas contracts make it difficult for the receiving country to switch to other sources or diversify.

This complicates the task of developing, marketing, and reaping geopolitical benefits from natural gas. Each country involved has diverging, and sometimes opposing, interests.

As we demonstrated in the case of Professor Gareth Stansfield, experts could not predict the complexity of the situation in the early stages of the industry. Gareth's piece was chosen primarily for his point of view, but also for his wider influence.

One distinguishing feature of KRG geopolitics is the KRG's difficulty in maintaining equal relationships with more than one neighboring country at the same time; for example, one of the core issues in the Erbil-Baghdad relationship is the KRI's relationship with Turkey. This is especially difficult when neighboring countries, such as Iran and Turkey, have a geopolitical rivalry. Furthermore, domestic politics is the cornerstone of any geopolitical ambition, especially in terms of gas. Gas delivery requires long-term stability.

Gas could be a source of stability and connectivity between Europe and Kurdistan. The EU Rather than spending billions on areas that have proven to only prolong crises rather than resolve them, make a strategic investment in KRI and wider Iraq, securing alternative gas supply routes while also wielding political power.

Footnote:

[1] https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/who-we-are/our-history/first-oil.html

[2] Black, Edwin. 2004. Banking on Bagdad: Inside Iraq’s 7,000-Year History of War, Profit, and Conflict. Wily.

[3] https://www.sciencespo.fr/ceri/fr/content/dossiersduceri/transformational-effects-oil-and-gas-strategy-kurdistan-regional-government-iraq

[4] https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-iraqi-kurdistan-agree-on-50-year-energy-accord-67428

[5] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2014/12/03/five-reasons-for-the-iraqi-kurdish-oil-deal/

[6] https://muse.jhu.edu/article/249196

[7] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v27/d24

[8] https://www.csis.org/analysis/turkey-and-krg-after-referendum-blocking-path-independence

[9] https://brill.com/view/journals/ic/26/2/article-p183_7.xml

[10] https://www.bakerinstitute.org/event/geopolitics-natural-gas

[11] https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iraqi-kurdistan-has-energy-capacity-help-europe-says-iraqi-kurdish-pm-2022-03-28/

[12] https://www.esiweb.org/pdf/news_id_412_5%20-%20Article%20Kemal%20Kirisci.pdf

[13] https://www.mfa.gov.tr/policy-of-zero-problems-with-our-neighbors.en.mfa

[14] https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/14058132.pdf

[15] Matthew Zais, Barozh Aziz, Rob Waller, Gas in Iraqi Kurdistan: Market Realities, Geopolitical Opportunities, The Washington Institute for Near East Studies, Jan 21, 2021: https://cutt.ly/lXLO0zV