Reha Ruhavioğlu: We thank Rudaw for inviting us to present the results of our research. Our presentation will be in Turkish, but there is a translation available, and the text is in English. Thank you for your attendance.

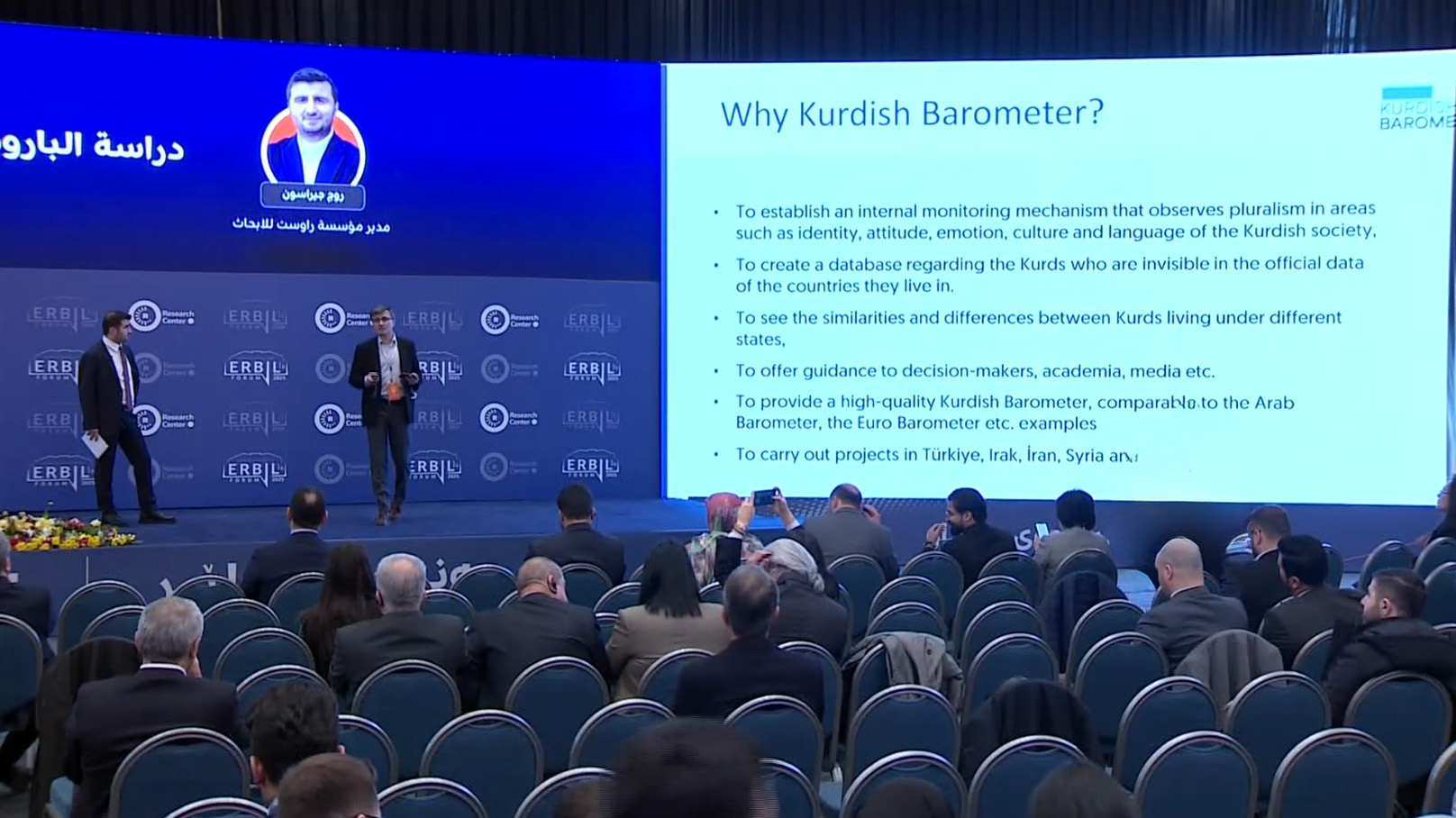

The Kurdish Barometer is a research project that started in Turkey. First, I would like to provide some brief information about the reason for launching this project.

This monitoring mechanism, or poll, is designed to track the attitudes and perspectives of Kurdish society on topics such as identity, emotions, cultural attitudes, and political participation in Turkey. Additionally, one of the main goals is to create a monitoring mechanism and database that specifically tracks data related to Kurds, as Kurdish data often gets lost within the official data of countries.

The project aims to understand the connections and differences among Kurds living under the authority of different countries. I believe this will serve as an essential guide for policymakers, academia, media, and international research centers.

This barometer was modeled after the Arab Barometer and European Barometer, intending to become a substantive and reliable monitoring mechanism for issues related to Kurds.

We have completed the first phase of the project, which focused on Turkey and have conducted our research. In future stages, we plan to expand this project to Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Europe. This means that in future phases, the project will grow and continue.

The issues and topics that we monitor in the Kurdish Barometer include the following, which you can see on the screen:

We monitor topics such as sociodemographics, identity, experiences of discrimination, feelings, and attitudes, attachment to the mother tongue, the status of the Kurdish language, the Kurdish issue in Turkey and related demands, political issues, participation in politics, relationships with politics, culture, and popular culture among the people.

Now, I would like to provide a brief overview of the Kurdish demographics in Turkey. We do not officially know the exact number of Kurdish residents in Turkey. Therefore, we rely on estimates and conclusions drawn from various research projects, which were used in this research. Today, different predictions and studies in Turkey suggest that approximately 20% to 25% of Turkey's population are Kurds. This corresponds to around 17 to 22 million people.

In Turkey, two-thirds of all Kurds live in their own region, in their own cities, which we refer to as the North. One-third of the Kurdish population has migrated to western Turkey. Those Kurds who have migrated to western Turkey are no longer just migrants; about half of the Kurds in western Turkey were born there. This means that the second generation of Kurdish migrants to western Turkey are now living there. However, this creates a series of differences. For instance, there are demographic and sociological differences between the Kurds in the Kurdish-majority regions and those in areas they migrated to in western Turkey.

The rate of mother tongue knowledge among Kurds in western Turkey is lower, but they are more integrated into Turkish politics through opposition movements. Additionally, those in the northern regions of Turkey have a distinct difference in terms of their native language. The Kurdish population in Turkey is young. Out of every 100 Kurds in Turkey, 60 are under the age of 30, compared to only 45% of the Turkish population in the same age range. Therefore, Turkey's Kurdish population is both young and energetic. Moreover, the family size among Kurds in Turkey tends to be larger.

Kurds in Turkey have a lower literacy rate. In terms of education and socio-economic conditions, they are at a disadvantage. However, I believe that Kurdish youth are steadily narrowing this gap with their Turkish counterparts. Today, the majority of Kurds in Turkey pursue higher education, which helps reduce the gap between Kurdish and Turkish youth, while simultaneously increasing the educational divide between the Kurdish youth and their parents.

Finally, one key takeaway is that the most underdeveloped and disadvantaged regions in terms of social and economic development are the provinces with significant Kurdish populations.

Government institutions in Turkey have categorized these areas into six different groups. The gray area you see on the map of Turkey is not Kurdistan; rather, it represents Turkey's most disadvantaged areas, which correspond to Kurdish-majority provinces.

If we look at how Kurds define themselves in terms of identity, they generally identify as democratic, Kurdish, and religious. In other words, Turkish Kurds possess a Kurdish identity, embrace democratic values, and maintain religious compatibility.

Regarding the acceptance of these three identities, approximately 40% of Turkish Kurds express more liberal and democratic attitudes, 30% exhibit more conservative tendencies, 20% prioritize Kurdish nationalism, and about 10% identify with secular and Atatürkist values. On a scale from 0 to 10, Kurdish nationalism scores an average of 5.41 out of 10.

When considering how Kurds view their emotional relationship with Turkey, we can categorize them into three main groups. One-third of Kurds in Turkey have a strong emotional connection with Turkey, another third feel a weak emotional connection, and the remaining group neither strongly identifies nor weakly identifies with Turkey.

When we study Kurdish nationalism in Turkey, we cannot refer to it as "Kurdish nationalism" in English. In fact, we cannot fully call it Kurdish nationalism at all. This is because Kurdish nationalism in Turkey takes on a different form.

I even wrote the word "nationalism" in English, which means that the sentiment we can refer to as Kurdish nationalism is indeed on the rise. However, it still lags behind Turkish nationalism when compared to the Turkish population.

The proportion of Kurds who identify strongly with nationalism is 31%, whereas the proportion among Turks is 60%. There are three key groups within Kurdish nationalism, while Turkish nationalism tends to have more individuals in the middle and high levels of nationalistic identification.

We also have a metric called the Kurdish Identity Ownership Index. This index is derived from a combination of various questions and variables. According to this index, two-thirds of Kurds living in Turkey strongly identify with their Kurdish heritage. Within this two-thirds, there are not only individuals who vote for Kurdish political parties, but also a broad and diverse group.

For nearly 10 years, since the previous solution process, Kurdish identity has been openly expressed in Turkey. This was not the case before. This openness has strengthened the connection to and ownership of Kurdish identity.

When examining Kurdish language usage in Turkey, we find that, out of every 10 Kurds, only 3 can speak Kurdish fluently. This means that less than 30% of Kurds in Turkey speak Kurdish proficiently. Additionally, another similar portion speaks the language at an intermediate level. As for the remaining four out of ten (or two-fifths), they either don't use the Kurdish language in their daily lives or have little to no knowledge of it. Kurdish identity is strongly connected to the Kurdish language. When the Kurdish language is strong, the connection to Kurdish identity is reinforced. Conversely, when the language weakens, we observe a corresponding deterioration in that connection.

Roj Girasun: Thank you. However, in Turkey, we see that the use of Turkish has declined across generations. This is partly due to the policy of assimilation, as well as factors related to modernization, civilization, and the weakening of language transfer.

Although the use of Kurdish has decreased, there has been no decline in demands for the use of Kurdish in education and public services. That is, even if the use of the Kurdish language has diminished, the demand for it from the state remains strong. We observe that about 80 out of every 100 Kurds request the use of Kurdish in both education and public services. This appears to be one of the common demands among nearly all Kurds, regardless of political affiliation.

As you know, for several months, Turkey has been undergoing a process related to demilitarization and the issue of disarmament, which has remained on the public agenda. Yesterday, Öcalan called for the dissolution of his organization. In our research, we regularly ask Kurdish society for their views on armed struggle. Approximately 65% of Kurdish society is firmly against armed struggle. Around 20% are uncertain and confused, while only 15% reluctantly support armed struggle, believing it is a necessary path.

In fact, we can observe that Öcalan’s call yesterday enjoys social support among Kurdish society.

Reha Ruhavioğlu: If we want to frame the Kurdish demands in Turkey in this way, when we look at the main demands, the issues and demands related to the Kurdish issue in Turkey can be classified as follows:

First, inequality and the elimination of inequality. This includes both ethnic discrimination, economic disparities, and sociocultural inequality.

Second, constitutional recognition—meaning there are expectations and demands for the official recognition of Kurdish identity.

Third, strengthening political participation and ensuring equality in the right to political participation. This can be broken down into demands such as the abolition of systems like the appointment of trustees (guardians), which would strengthen political participation. The ability for broad political participation is a key issue here.

Another important issue is ensuring the right to learn and speak the Kurdish language, as Mr. Roj mentioned earlier. As we emphasized before, the final resolution of the Kurdish issue remains one of the greatest demands in Turkey. In this way, we can establish a framework for Kurdish demands in Turkey.

Roj Girasun: Now, we asked to what extent Kurds support these demands, especially those related to the Kurdish language. The percentage of Kurds who say that Kurdish children should study in their own language in schools has reached 73%, and this is the minimum level. The percentage of those who say Kurdish identity should be recognized in the constitution stands at 71%. The percentage of those who say Kurdish should become an official language is 60%. The percentage of those who say Kurdish cities should be economically developed rises to 81%. This is also the same percentage of those who say there is inequality. The percentage of those who say the powers of local administrations should be increased is 75%. The percentage of those demanding autonomy for Kurds is at 60%.

The issue of Turkishness is something I’m not sure should be translated as "becoming Turkish" in Kurdish, but it is a topic frequently discussed. This issue is both on the Kurdish political agenda and has been debated by Kurdish intellectuals for some time. Over the years, we’ve been asking this question to Kurdish society and trying to measure the changes in attitudes toward it. What we observe is that support for the policy of “becoming Turkish” or embracing “Turkishness” has increased, and we see that this support has also risen among Kurds who vote for different political parties.

Reha Ruhavioğlu: We will now present some brief data on Kurdish culture in general and may conclude with that.

The strongest connection of the Kurds with their language is through music. About 85% of Kurdish adults in Turkey listen to Kurdish music, to varying degrees, in their daily lives. Additionally, about half of the adults report having watched a Kurdish film at least once in their lifetime. Forty-four percent say they have attended a Kurdish concert at least once, and one-third claim to have read at least one Kurdish book. These last three percentages may appear low, as they count even those who have engaged with these cultural elements just once in their lives. However, music is something that is widely enjoyed every day.

Now, let’s take a look at those who listen to music. When we examine the data on what music and artists they prefer, the results are telling. Among the top five names, we still see the traditional figures of the Kurdish music world. However, the list has become more diverse, younger, and modern. For instance, Ahmet Kaya, Şivan Perwer, and Jawan Hajo, as traditional artists, have retained their spots, while new artists such as Aynur Doğan, Mam Ararat, and Rojda have emerged on the list. This shows that Kurdish music is evolving to become more diverse and contemporary.

However, when we look at the preferences of Turkish Kurds regarding food, we see that their tastes remain deeply rooted in tradition. While Kurdish music has modernized and diversified, food preferences have largely remained unchanged. The most popular dishes are still dolmas, kebabs, and meat dishes. In other words, when discussing Kurdish cuisine, these are the first dishes that come to mind.

Roj Girasun:

Now, in our discussions about the Kurds in Turkey—discussions we've been having for a long time—a clear difference has emerged. There is now a noticeable distinction between the Kurds of the region and the Kurds of the west. That is, Kurds from western Turkey versus Kurds from northern Kurdistan.

A social and political divide is deepening between the Kurds living in Turkey's western metropolises and those in the region. While Kurdish identity and party-related identities are expressed more strongly among Kurds living in the region, an oppositional identity is becoming more prominent among Kurds in western Turkey. For example, there is a growing approach toward the Republican People's Party (CHP), reflecting a desire to align with the Turkish opposition.

The second issue is the matter of "becoming Turkish." This is a serious topic of discussion and one that needs to be emphasized once again. We see that this issue has emerged more as a process than as a project that has shaped Kurdish politics. Society has shown a tendency to lean toward becoming Turkish, and this tendency is evident socially. Perhaps only politics can now turn this into a concrete project.

Another issue relates to the use of the Kurdish language, which is again an important point that should be highlighted. In Turkey, there is often criticism and debate that Kurds do not speak Kurdish, are distanced from the Kurdish language, and lack Kurdish identity. This argument can be made, but we can still clearly state that, in Turkey, while Kurdish identity has weakened culturally, it has not regressed politically.

This issue of civilization and Turkishness, which has emerged in this study and others, has led us to new considerations. Additionally, in other comprehensive studies that analyze the data, we see the phenomenon of Selahattin Demirtaş, who has recently emerged strongly in these studies. This may be because Demirtaş has become a spokesperson and an icon of the process of civilization, democratization, and Turkishization of Kurdish society.

Reha Ruhavioğlu:

Yes, we have reached the end. Thank you very much for listening. That was all we wanted to discuss.

I'm not sure if there is a question and answer format in this program, but if there is, we can answer a few questions. If there are any questions… I guess not. Alright, thank you.