Divided Victory in Iraq’s 2025 Election and an Uncertain Government Formation Process

16-11-2025

Iraq’s contentious 2025 election unfolded amid deep internal fractures—across ethnic, sectarian, and political lines—and within a broader regional environment marked by heightened geopolitical tension. The preliminary results of the political balance translate into a new configuration that may include the following

Within the Shiʿa political arena, two dynamics dominate the landscape. On one side looms the enduring influence of Muqtada al-Sadr, whose withdrawal from formal politics has not diminished his movement’s capacity to mobilize or disrupt. On the other side, intensified rivalries among established Shiʿa factions have made Prime Minister Mohammed Shiaʿ al-Sudani’s path to retaining his position far more challenging than before.

Although Sudani’s coalition achieved notable numerical gains, these do not automatically translate into strategic leverage. Instead, Qais al-Khazali, leader of Asaʿib Ahl al-Haq and a central figure within the Coordination Framework, has emerged as the principal Shiʿa winner in terms of bargaining power and ability to shape post-election alliances. His bloc’s expanded influence strengthens the position of the armed-network political formations often referred to collectively as the “resistance factions.”

Additionally, the improved performance of groups linked to armed organizations—as well as the political resurgence of Ammar al-Hakim, whose list fared considerably better than in 2021—will directly shape Iraq’s domestic and foreign policy orientation.

Both major parties in the Kurdistan Region—the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)—have consolidated their positions within the Region’s internal political landscape. This can impact the balance and their necessary partnership for forming the government. While the Kurdish parties remain dominant within the autonomous Region, this dominance does not automatically extend to the disputed territories outside the KRI—such as Kirkuk, Nineveh, and parts of Diyala, and their leverage in Baghdad may also weaken if internal divisions between the KDP and PUK widen.

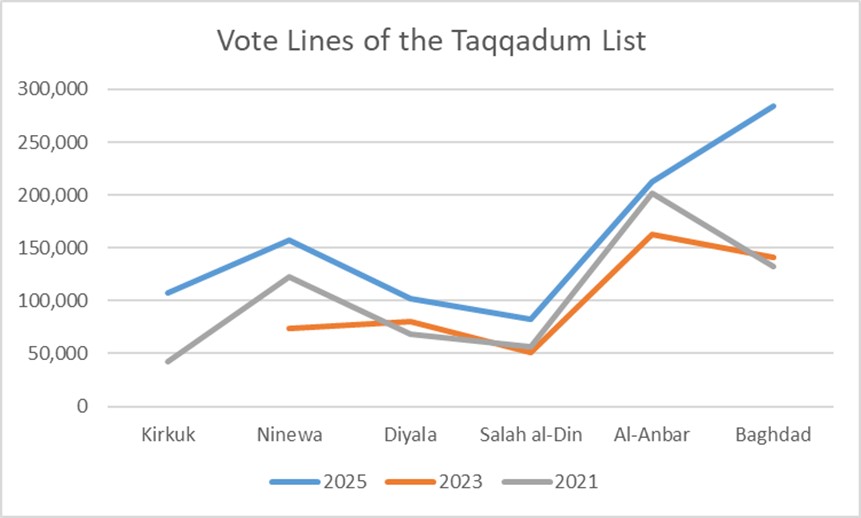

Among the Sunni political blocs, Mohammed al-Halbousi has re-emerged with significantly greater strength. His increased vote share in Baghdad enhances his bargaining position with major Shiʿa factions. Additionally, his growing presence in Kirkuk, a province central to Kurdish–Arab competition and to the long-standing disagreement between the KDP and PUK, means that Halbousi may play a direct or indirect role in shaping the balance between the two Kurdish parties. Also, his influence will extend into negotiations over the distribution of key positions.

Numerical victory vs. strategic victory within the Shiite camp in the recent election

Sudani emerged as the numerical winner in the election, with his alliance securing first place among Shiite blocs. However, despite this electoral lead, he remains far from guaranteeing his political future as prime minister. Following the results, he appeared on camera with a face that seemed either exhausted, sleepless, or concerned. He offered his congratulations and stated that his alliance is ready to begin dialogue on forming the next government. This was an indirect signal that he hopes to retain the premiership. Yet Hadi al-Amiri, the head of the Badr Organization and a central figure in the Shiite political landscape, appeared to undercut him in advance by declaring that Sudani had not actually requested a second term.

In reality, Sudani’s challenge is far more complex. His eight-party alliance must navigate and accommodate several major power centers within the broader Shiite camp—actors whose political weight, organizational networks, or militia influence give them significant leverage in government formation negotiations.

- Armed Groups:

This includes factions long involved in formal politics—such as the Badr Organization, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and Kataib Hezbollah—as well as armed groups that entered these elections through independent lists or newly formed alliances. - Traditional Shiite Parties:

To remain in power, Sudani must also satisfy the traditional Shiite political establishments, most notably Ammar al-Hakim and Nouri al-Maliki. Appeasing Hakim may prove less difficult; his alliance secured 4.27% of the vote in these elections, giving him influence but not dominance - Sadr and the House of Ayatollah Sistani:

Sudani must also remain mindful of Muqtada al-Sadr and the religious establishment tied to the house of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. Although both currently maintain an official distance from day-to-day politics, their moral authority and ability to mobilize public sentiment mean they cannot be ignored.

Sadr’s Boycott Benefits Sudani

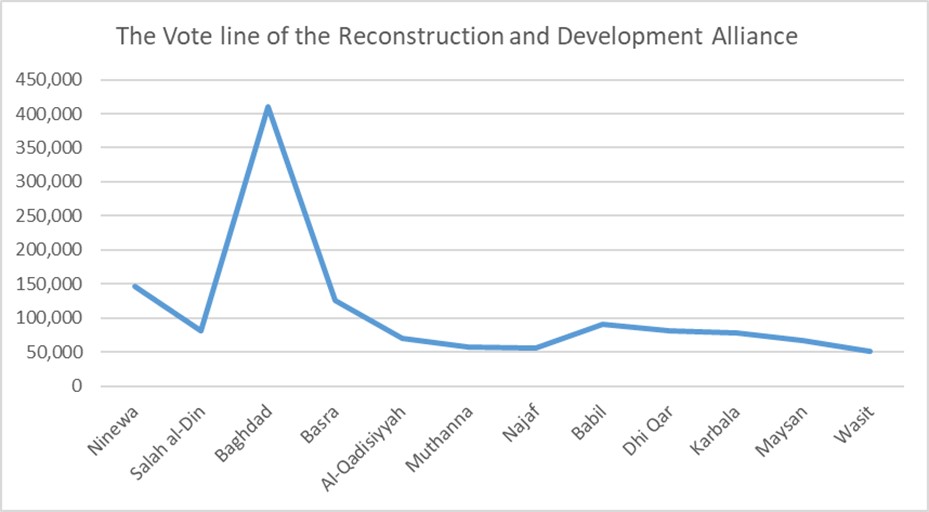

Sudani’s alliance secured roughly 9% of the proportional vote across 12 provinces, achieving its strongest results in Wasit, Maysan, Karbala, and Dhi Qar. Notably, his coalition came in first place in six of the eight provinces where the Sadrist movement had dominated in the 2021 elections. Although Muqtada al-Sadr has denied providing any covert support to Sudani’s list, the results suggest that Sadr’s election boycott indirectly benefited the Reconstruction and Development Coalition led by Sudani.

This election was as much a litmus test for Sudani as it was for Sadr and his call for a boycott. According to official statistics released by the Independent High Electoral Commission, the boycott was not uniformly observed. The outburst from one of Sadr’s ministers over a video featuring Sheikh Mahdi al-Karbalai—who encouraged citizens to participate—underscored the tension between the campaigns advocating participation and those urging abstention.

In any case, turnout in Shiite-majority provinces was the lowest in the country, a political signal that any future government will need to take seriously.

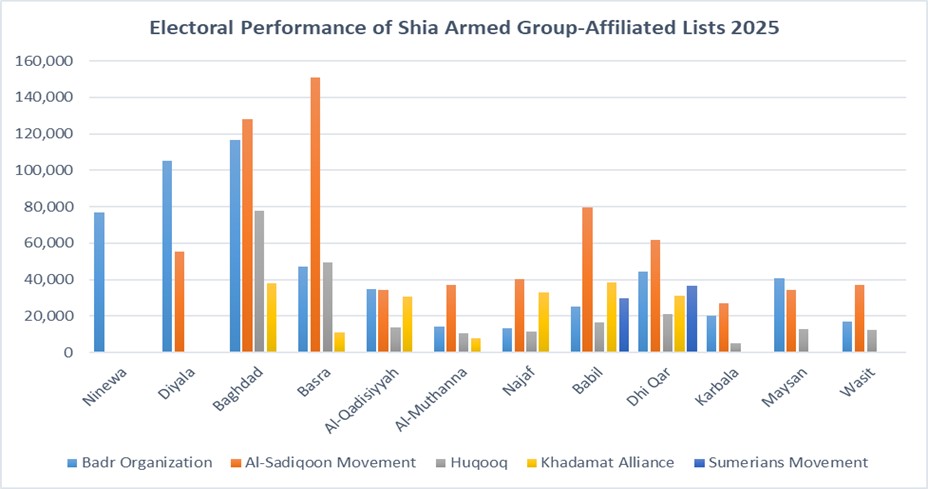

The consolidation of the armed groups’ position

Excluding the Montaseroun bloc of Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada—which participated as part of Nouri al-Maliki’s coalition—and aside from Faleh al-Fayyadh, who ran within Sudani’s alliance, Shiite armed groups collectively secured 1,729,566 votes across 12 provinces. The results indicate that, following Sadr’s boycott, southern Iraq remained the main stronghold of these factions, reinforcing their influence and electoral resilience.

In Basra, four major groups—Sadiqun (the political wing of Asaib Ahl al-Haq), Badr, Huqooq (affiliated with Kataib Hezbollah), and Khadamat (linked to Kataib Imam Ali)—collectively obtained 258,823 votes, amounting to nearly 16% of the province’s total vote count. Sadiqun was the clear front-runner among them, securing more than 150,000 votes on its own, underscoring its enduring organizational strength in the province.

In Diyala—a province of strategic significance due to its geographic location and its function as a corridor for the armed groups’ military and logistical movements—Badr and Sadiqun combined to win 15.38% of the total votes. Their continued influence in Diyala reflects both entrenched local networks and the security environment that has long given these groups a strong foothold.

The Sumeriyoun list, aligned with Kataib Jund al-Imam, showed notable presence in Dhi Qar and Babylon or Babel. However, Huqooq distinguished itself by establishing a more solid and consistent base across all ten southern provinces.

Across these 12 provinces, Sadiqun outperformed all other armed factions in nine of them, a pattern that underscores the rising political weight of Asaib Ahl al-Haq. If Sudani now stands as the numerical frontrunner among the Shiite lists, one could argue that Qais al-Khazali is the strategic winner of the election—quietly but steadily positioning himself as a potential future leader of the Shiite political arena. The age factor reinforces this trajectory: Nouri al-Maliki is 75, Hadi al-Amiri is 71, and Faleh al-Fayyadh is 69, while Khazali is only in his early fifties. Meanwhile, Muqtada al-Sadr’s oscillation between political withdrawal and religious engagement has created a leadership vacuum—one that offers Asaib Ahl al-Haq a rare chance to expand its influence and potentially claim a more central role in Shiite politics, especially if the current political landscape persists.

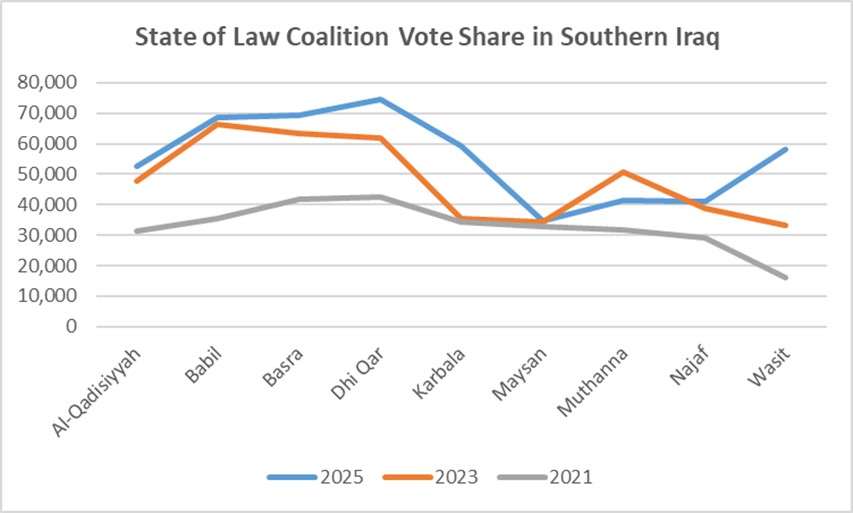

As for the State of Law coalition, a comparison of its results in the 2021, 2023, and 2025 elections shows that it has largely preserved its traditional base in Dhi Qar, Babylon, Wasit, and Karbala. It has also increased its vote share in most southern provinces, with the exception of Muthanna. This performance allows State of Law to continue seeing itself as a frontline contender. However, its main challenge is the intensifying competition. In 2021, its primary rivals were the Sadrists and the Fatah Alliance. In 2023, a new challenger emerged in the Nabni Alliance. In 2025, from Sudani’s coalition and beyond it, Asaib Ahl al-Haq and other rising actors forced State of Law into close, multi-sided contests across almost all southern provinces.

These results may represent a significant obstacle to Maliki’s prospects for returning to the premiership. Yet he remains almost certain to be among the key power brokers involved in shaping the selection of the next prime minister.

Government formation amid external and internal dynamics

Because the formation of the Kurdistan Regional Government is closely tied to the political situation in Baghdad—and because the Sunni blocs remain fragmented—the prospect of assembling a supra-sectarian alliance that would benefit Sudani, similar to the 2021 coalition, appears politically unlikely. From a numbers standpoint, securing the two-thirds majority required to convene parliament is nearly impossible without first satisfying the core Shiite actors.

Analyses that frame the question of Sudani’s continuation in office primarily through the lens of U.S.–Iran competition tend to b fanciful. Certainly, each side would prefer a prime minister aligned with its interests, but while the identity of the Iraqi premier may hold considerable importance for Iran, it matters far less for a Trump-led United States. Moreover, Washington has sufficient leverage in Iraq to secure its key demands regardless of who occupies the premiership. For Iran, the problem is that this election, 2025 Iraqi parliamentary election was more about internal competition among the groups within the Coordination Framework in the south, which itself played a role in bringing the Framework together. It has relationships with many of the competing forces in this election who are within that Framework, and it may be best for it to bring them together again through that same mechanism.

Proportionally, Iraqi governments formed after the fall of Saddam have typically required six to seven months to come together, with the fastest formation occurring in 2014, which took just over four months, and the slowest in 2021, which stretched to thirteen months. Current indicators suggest that this round of government formation may be comparatively smoother. One reason is that most of the principal rival parties were already participating in the outgoing government, reducing ideological barriers and easing negotiations. In the Shiite arena, the existence of the Shiite Coordination Framework—now an established mechanism for organizing and negotiating among Shiite factions—further simplifies the process. However, internal bargaining over cabinet shares is likely to intensify, as each faction’s expectations for political influence have grown alongside their electoral performance

Kurds and Sunnis: current political dynamics

Among the Sunnis, Mohammed al-Halbousi has staged a strong political comeback after his removal from the speakership of parliament. He has succeeded in reasserting himself as a leading Sunni figure and in projecting influence beyond his traditional base in Anbar. This resurgence could significantly strengthen his position in government formation negotiations—particularly because in a strategically sensitive and contested province like Kirkuk, he has increased his vote share by more than 150% compared to 2021.

On the Kurdish front, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) has emerged strengthened, a development that will shape the dynamics of forming the next Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). It was an open secret that the failure to form the KRG after the last regional elections was tied directly to political calculations surrounding the Iraqi national elections. The new results bolster the KDP’s negotiating hand and may embolden its stance vis-à-vis the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). However, the PUK and its allies have expanded their influence in Baghdad, which may counterbalance the KDP’s gains and force some degree of mutual accommodation.

Some time ago, Qais al-Khazali publicly expressed at the PUK congress in Sulaymaniyah his hope that Bafel Talabani would become President of Iraq—signaling his willingness to play a role in shaping the Kurdish internal balance and positioning himself as a potential broker. This time, however, it is not only Shiite actors who may influence the Kurdish equation; Sunni Arab leaders may also exert pressure. Halbousi has for some time spoken about the idea of a Sunni holding the Iraqi presidency and has adopted a more confrontational tone toward Erbil. His significant electoral gains in Kirkuk further widen his political options.

With a multi-headed cabinet led by the Coordination Framework and its various factions, tensions between Baghdad and Erbil are expected to persist. Beyond the longstanding disputes over salaries, the federal budget, and oil exports, additional issues continue to complicate relations—namely the presence of American forces in Iraq and the possibility of a hypothetical U.S. strike on armed groups operating along the Iraq–Syria border. These factors remain constant pressure points that can influence Baghdad–Erbil dynamics regardless of electoral outcomes.

Another important development is that the election results have pushed the Kurdish position in certain disputed territories—particularly Kirkuk—toward even greater uncertainty. For the first time, Kurdish-held seats in the province have fallen to below half of the total. While territorial disputes are not usually resolved through elections but through the balance of military and political power, shifts backed by electoral legitimacy can have a more durable effect. Had all Kurdish parties in Kirkuk run on a unified list, they would have secured 252,736 votes, translating into a higher proportion of seats. Instead, their collective vote total declined compared to 2023, when all Kurdish lists combined reached 290,635 votes. This indicates that the Kurdish parties not only failed to unite but also struggled to mobilize their full voter base in 2025.

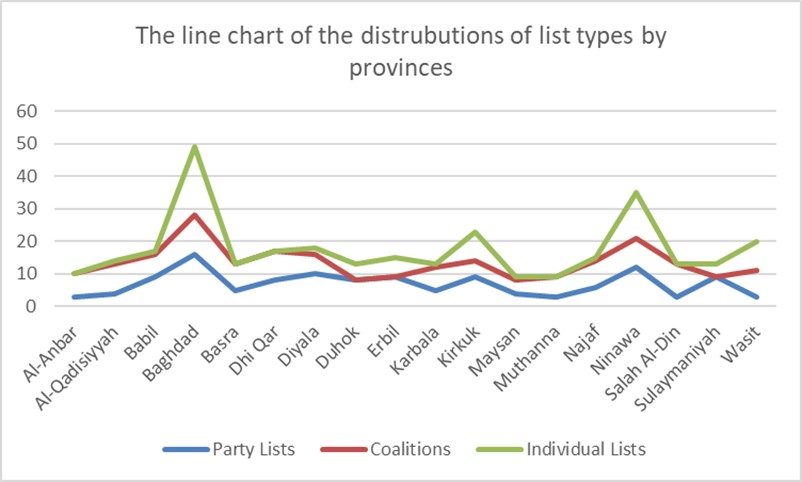

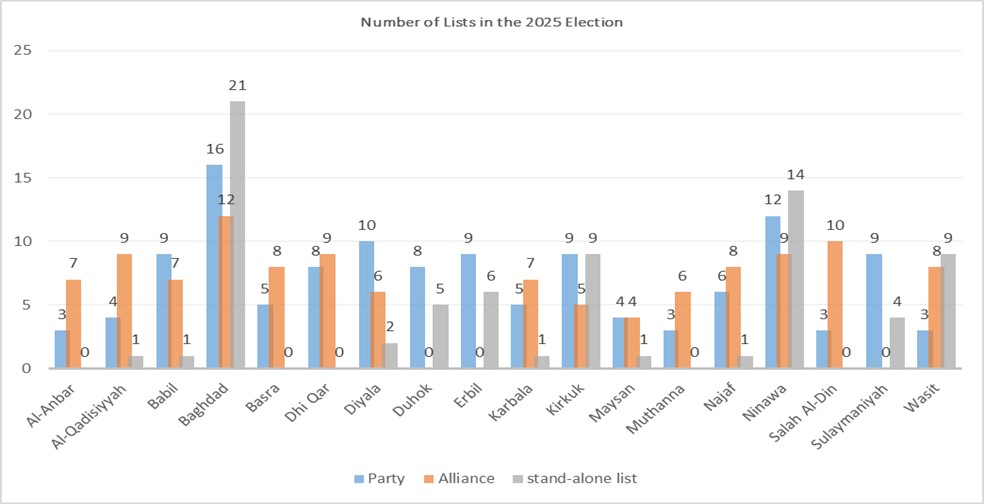

The escalation of internal divisions and polarization prevented Kurdish parties from forming alliances in this election cycle, leading them to swim against the prevailing political tide in Iraq. In contrast, nearly all major Shiite and Sunni groups—aside from a few factions among the armed groups—participated through broad alliances. Even in strategically significant provinces such as Baghdad, Kirkuk, and Nineveh, these forces formed joint lists, despite competing separately in other areas. The Kurds’ refusal or inability to adopt a similar strategy significantly diminished their influence in the most politically contested regions.

Participation as a long-term challenge for the system

The High Electoral Commission announced a participation rate of 56.11%, stating that 12,009,453 people voted. While this figure is accurate if measured against the 21,404,291 registered voters, it represents only 41.13% of the estimated 29.2 million eligible Iraqis who could have participated. In practical terms, six out of every ten eligible citizens did not vote. Over the long term, this level of disengagement represents a serious, structural challenge to the legitimacy and durability of Iraq’s political system.

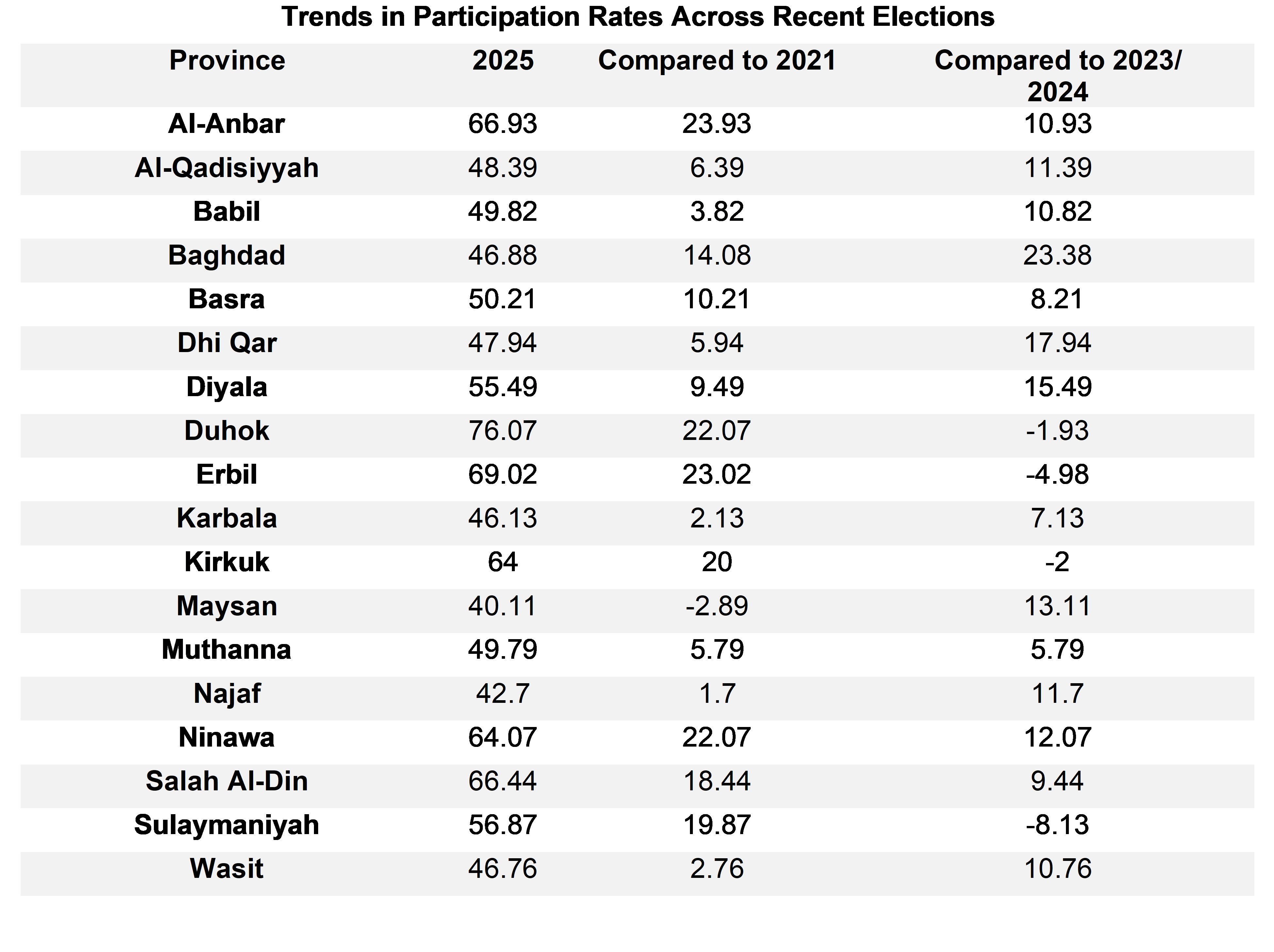

According to the official results, overall voter turnout increased by 8.39% compared to the 2023 provincial council elections and the 2024 Kurdistan Parliament elections, and by 11.60% compared to the 2021 parliamentary election.

Based on turnout patterns from the 2023–2024 Iraqi provincial elections and the 2024 Kurdistan parliamentary election, participation was comparatively higher in Baghdad, Nineveh, Diyala, Anbar, and Salah al-Din. Although Kirkuk and the provinces of the Kurdistan Region remained among the areas with the highest turnout, their participation levels declined relative to their previous elections—most notably in Sulaymaniyah, which recorded the sharpest drop.

Broadly speaking, Sunni-majority provinces showed a noticeable rise in participation, potentially reflecting renewed political mobilization, shifting alliances, or clearer stakes in the outcome. In Shiite-majority provinces, turnout also increased compared to recent elections, but these areas still registered the lowest participation rates in the country. Provinces such as Najaf and Maysan remain at the very bottom of the turnout list.

Unemployment, poverty, living conditions, or other factors

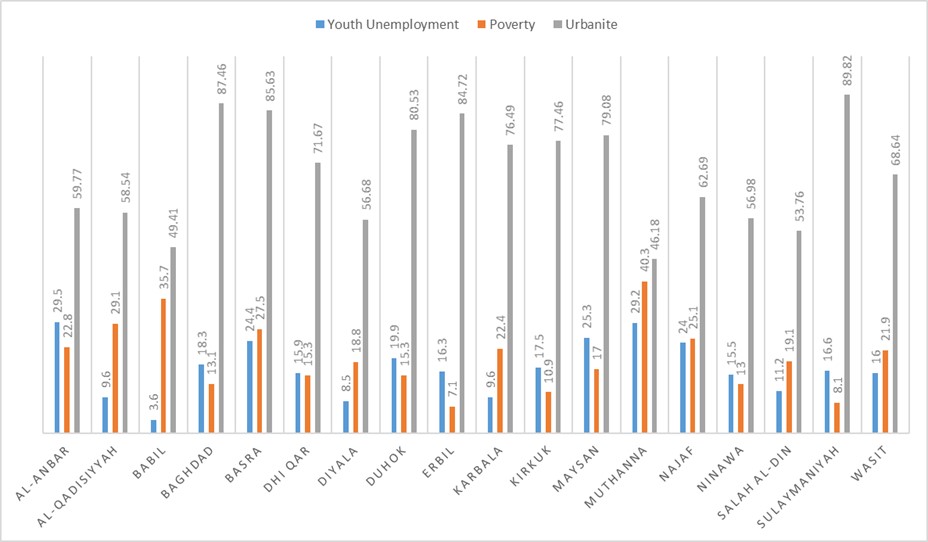

It is unlikely that any single factor can fully explain the variations in voter participation across Iraq’s provinces. The data reveal patterns, but also contradictions that point to the influence of deeper political and social dynamics.

In provinces such as Anbar, Muthanna, Duhok, Maysan, Kirkuk, and Baghdad, which have some of the highest rates of youth unemployment, turnout was generally high—with the exception of Maysan, where participation remained around 40%. Conversely, in Babylon, Diyala, Qadisiyah, and Karbala, which have some of the lowest youth unemployment rates, turnout stayed below 50% in all but Diyala.

Poverty indicators also present mixed results. Duhok, which has the highest poverty rate, and Erbil, which has the lowest, both recorded high electoral participation. Among the ten provinces where poverty levels fall below the national average of 20%, turnout dropped below 50% in all except Erbil, Kirkuk, and Nineveh. Conversely, in those places where poverty is higher, except for Najaf, in 7 other provinces the participation rate was above 50%.

Urbanization patterns likewise show inconsistency. In the nine provinces where the urbanization rate is below the national average (69%)—and rural life is more predominant—the outcomes diverge sharply. In Sunni-majority provinces, turnout was high, while in Shiite-majority provinces with similar rural characteristics, turnout remained low. This suggests that Sunni political actors were more successful than their Shiite counterparts in mobilizing rural populations. Meanwhile, in provinces with urbanization levels above the national average, Kurdish-majority cities recorded high turnout, but Shiite-majority cities did not.

Even the level of political competition, which has increased participation in earlier elections, did not produce a uniform effect this time. In Duhok, which had the fewest candidates (only 59), turnout was high. In contrast, Baghdad—with 2,299 candidates from 49 parties, alliances, and independent lists—still saw participation remain below 50%. The assumption that more competition inevitably mobilizes voters does not hold in this election cycle.

It is here that it becomes clear that the issue of participation by those who participated cannot be explained solely by economic factors. Although these may be useful for understanding the real rate of non-participation, which amounts to around 60%, the main reason for the turnout of that portion who voted may relate to other matters such as political factors like the level of political polarization, the parties' ability for social mobilization, and the relationship between tribe-ideology and politics.