The Vulnerability of the Iraqi Energy Sector amid Shifting Great-Power Rivalries

10-12-2025

Overview

In recent days, Iraq's Oil Ministry officially invited U.S. companies to acquire Lukoil's stake in the West Qurna-2 oil field. A halt or disruption in production there — and a resulting suspension of exports amounting to some half a million barrels per day — would be very difficult and potentially disastrous for Iraq. That is especially concerning at a time when global oil prices have declined, and current revenues may no longer be sufficient to cover Iraq's expenditures.

Meanwhile, investment by Chinese firms in Iraq's oil and gas industry has surged. Today, a substantial portion of this critical sector — which underpins the Iraqi economy — is managed by Chinese companies. According to recent estimates, Chinese investments in Iraq amount to around US$30 billion across various segments, including exploration, drilling, and production. As a result, we can say that roughly one-half to two-thirds of Iraq's energy sector is now operated by Chinese companies.

Now, Iraq — despite having asked the United States for a one-year sanction waiver to allow the Russian Oil company to continue oil production at the West Qurna-2 oilfield — is engaged in direct talks with ExxonMobil and Chevron about acquiring the field. This oilfield is currently operated by the Russian Public Joint-Stock Company Lukoil, which holds a 75 per cent stake and manages daily operations.

In recent months, ExxonMobil signed a memorandum of understanding to develop the Majnoon oilfield and is now reportedly in talks to acquire Lukoil's stake in West Qurna-2. Iraq appears to prefer assigning the West Qurna-2 stake to ExxonMobil rather than Chevron, making Exxon — the largest U.S. energy company — likely to become the operator of a substantial portion of Iraq's oil production in the near future.

Taken together, these developments highlight the diversification of Iraq's investment environment and the country's opening to the world's largest energy companies. However, the case of the West Qurna-2 oil field reveals a major structural weakness in Iraq's energy sector: its vulnerability to shifts in the relationships among global powers. It raises a critical question: if, one day, the United States were to impose sanctions on China and its energy companies, how would Iraq continue to produce oil and finance the state, given that around 90 per cent of government revenue still comes from oil exports?

West Qurna-2: As Russia Steps Back, Is the United States Returning?

The West Qurna‑2 oil field, located northwest of Basra in southern Iraq, is among the largest oil fields in the world. Its initial recoverable reserves are estimated at around 14 billion barrels, making it one of the country's geologically richest formations. In December 2009, the Russian energy company Lukoil was awarded the contract to develop West Qurna-2, and in early 2010, it signed a service contract to begin development and production. Commercial production from the field started on March 29 2014. At its peak output in recent years, Lukoil drilled dozens of wells (57 in 2019), and the field's production capacity reached about 480,000 barrels per day.

Lukoil holds a 75% interest in West Qurna-2, while the remaining 25% is held by the Iraqi state-owned North Oil Company (NOC), under the authority of the Iraqi Oil Ministry. However, following the tightening of sanctions by the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) — part of broader restrictions targeting the Russian energy sector — the future of Lukoil's operations at West Qurna-2 has become uncertain. As a result, the Iraqi government is reportedly seeking a mechanism either to end Lukoil's involvement or ensure continued production under a different operator, possibly involving the sale of Lukoil's stake to a non-Russian entity.

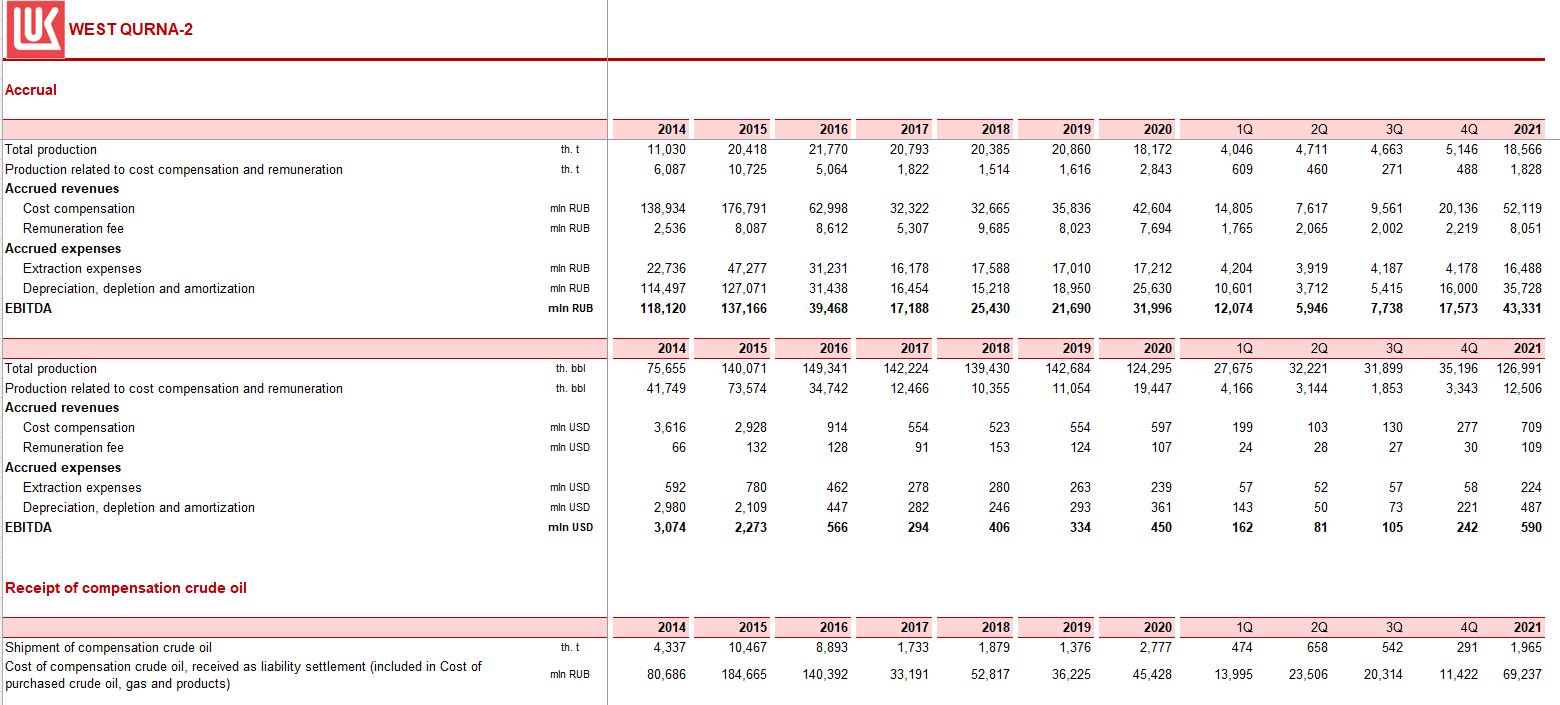

Table 1: Lukoil's Production, Costs, and Revenues from the West Qurna-2 Oil Field, 2014–2021

Source: Lukoil Annual Financial Report 2021. File accessed on December 2 2025. No updated report has been published since 2022.

In fact, the sanctions have been so effective that, less than a month after the U.S. measures were announced, the Russian company confirmed that Iraq had suspended all cash and crude oil payments to it. As a result, the company is likely to withdraw from the West Qurna-2 oil field, as U.S. and British sanctions have effectively cut it off from international operations.

At the same time, both ExxonMobil and Chevron are engaged in discussions with the Iraqi Oil Ministry—at the Ministry's invitation—regarding the potential transfer of operatorship of the field. Current indications suggest that the Ministry is inclined to award the project to ExxonMobil; if not, it is likely to go to another U.S. company. ExxonMobil, which withdrew from the field in early 2024, could return after the required two-year interval. If it does, the company would ultimately account for roughly one-quarter of Iraq's total oil production, or about 1 million barrels per day.

Another possibility would be to reach a U.S.–Russia–Ukraine ceasefire agreement. In that scenario, sanctions could be lifted, allowing the Russian company (Lukoil) to resume normal operations and continue receiving wages and profits. According to Lukoil's 2021 data, the company received USD 709 million in cost compensation and remuneration fees and incurred USD 224 million in extraction expenses. In return, the company was allocated 13.4 million barrels of compensation crude oil and generated USD 590 million in revenue (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation – EBITDA).

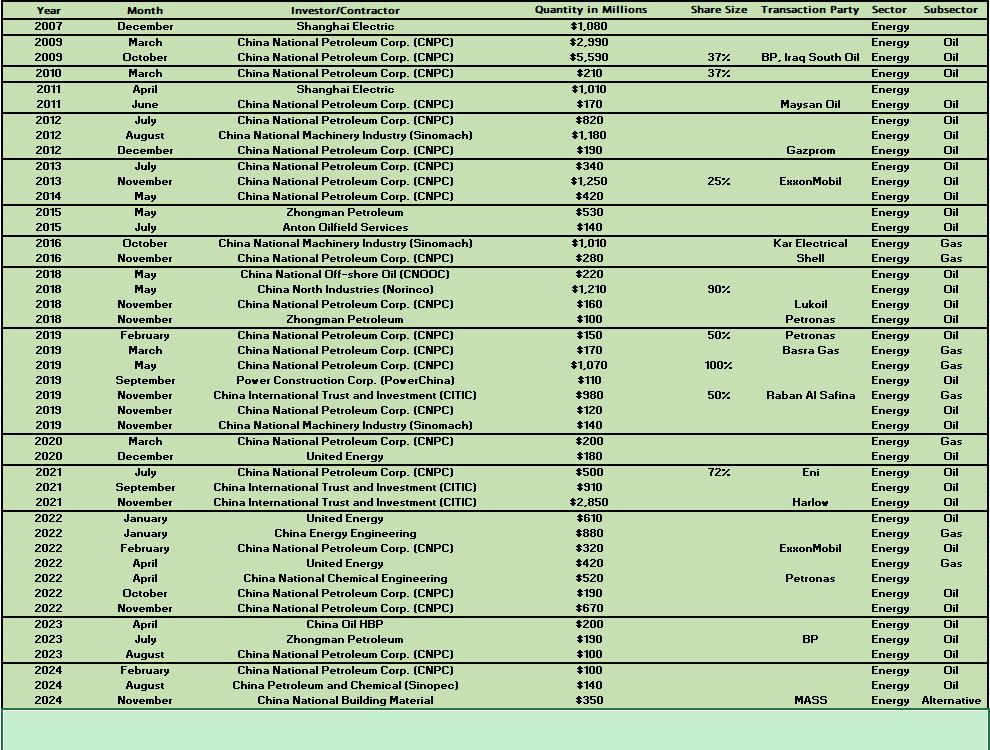

China's Investment in Iraq's Energy Sector: Oil and Gas, 2005–2024

According to available data, China's total investment in Iraq's energy, real estate, tourism, and transportation sectors reached US$35.4 billion between 2007 and 2024, with more than US$30 billion going specifically into the energy sector. Chinese companies have been active in Iraq for over two decades. Still, as shown in the table below, the most significant growth has occurred in the oil and gas sector, mainly driven by China's rising demand for Iraqi crude oil.

For example, if annual trade between China and Iraq were to reach about US$50 billion, this would broadly reflect Chinese imports of Iraqi crude — potentially more than US$35.2 billion.

A distinguishing feature of Chinese companies, compared with U.S., European, or British firms operating in Iraq's energy sector, is the close relationship between these firms and the state. As a result, geopolitical or diplomatic disputes involving China can also affect Iraq's oil and gas industry — especially given that a substantial portion (in some estimates, half or two-thirds) of Iraq's oil and gas production is now managed by Chinese firms.

Table 2: Investment and Operations of Chinese Companies in the Iraqi Energy Sector, 2007–2024

Source: Derek Scissors, Senior Research Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), founder of the China Global Investment Tracker — accessed December 4 2025

Note: Some investments reflect joint ventures or partnerships with large global companies; equity ratios, where available, are indicated alongside the investment amounts.

Conclusion

Now, with West Qurna-2 under threat—facing a production shutdown one day and an export shutdown the next—Iraq essentially has two choices if it wants to continue securing roughly half a million barrels per day from the field. The first option would be to transfer or sell Lukoil's stake to U.S. companies. The second hinges on a ceasefire in the Ukraine–Russia war (or lifting of sanctions), so that Lukoil's operations and contracts can resume. Both alternatives underscore how vulnerable Iraq's energy sector has become — heavily dependent on external geopolitical developments.

In the future, as the role of Chinese companies in Iraq becomes more complicated, the situation could become even more complex. If the United States and China fail to renew the agreement previously reached in South Korea and geopolitical and economic rivalry intensifies again, the fragility of Iraq's energy sector will become even more apparent. Under such circumstances, enabling Chinese companies to fill the investment, production, and operational gaps in Iraq would not only be difficult but potentially impossible. This is especially significant given that Chinese investment and activity in Iraq already rival — and in some areas far exceed — those of Russian companies, by a factor as high as 30.

In sum, although Iraq has tried to diversify its energy investment partners, this strategy may have inadvertently weakened the stability of its energy sector. In the event of a renewed conflict between major global powers — particularly those providing capital and expertise — Iraq's economy could face extreme disruption.