Iraq’s Economy, 2015–2025: How Did Public Expenditure Rise from 2.8 Trillion to 9.1 Trillion Dinars in a Single Month?

30-01-2026

Overview

Data published by Iraq’s Ministry of Finance provides an official view of how the country’s economy has been managed over the past decade, with one defining feature standing out clearly: the sustained and rapid expansion of public expenditure. This report is the first installment of a three-part series examining Iraq’s economic trajectory, based on the Rudaw Research Center’s monthly revenue and public expenditure dashboard covering all state institutions from 2015 to 2025.

This section focuses on two central questions. First, how did public expenditure in Iraq expand to its current levels, and is this trend likely to continue? Second, can an economic model so heavily dependent on public expenditure remain sustainable into 2026?

During this period, Iraq’s Supreme Financial Council convened more than four consecutive meetings aimed at reducing public expenditure and increasing state revenues. However, the fiscal data point to a different reality. Public expenditure has continued to rise year after year, while oil revenues—along with fluctuations in global oil prices—remain the primary foundation of the state’s income

According to data from Iraq’s Ministry of Finance, total government expenditure in the first month of 2015 amounted to just 2.8 trillion Iraqi dinars. In the same month of 2020, expenditure had risen to 5.1 trillion dinars, and by the first month of 2025, it exceeded 9 trillion dinars. Taken together, these figures indicate an increase of more than 200 percent over the period, with the entirety of this growth driven by operational expenditure. For the first month of 2026, this article presents projections of total expenditure under three different scenarios, derived from trends observed in previous years.

At the same time, it is important not to overlook the widening gap between expenditure and revenue toward the end of last year. This imbalance reached a level that prompted the government to freeze public-sector employment, promotions, and allowances for senior positions. According to the Iraqi Prime Minister, salary expenditures for senior-level officials—from director-general positions up to the three presidencies—amount to approximately 500 billion dinars per month, or about $384 million.

Despite these measures, the continued rise in expenditure, combined with Iraq’s heavy dependence on oil revenues as the sole source of income, suggests that policies focused on suspending promotions, reducing senior salaries, or halting public employment are unlikely to provide a lasting solution. At best, as the Kurds say, such steps merely “patch the problem” temporarily. The underlying drivers of expenditure growth are broad-based, overwhelmingly concentrated in operational spending, and deeply embedded in an economic structure that remains dependent on state expenditure.

Key Drivers of the Increase in Public Expenditure: January 2015, 2020, and 2025

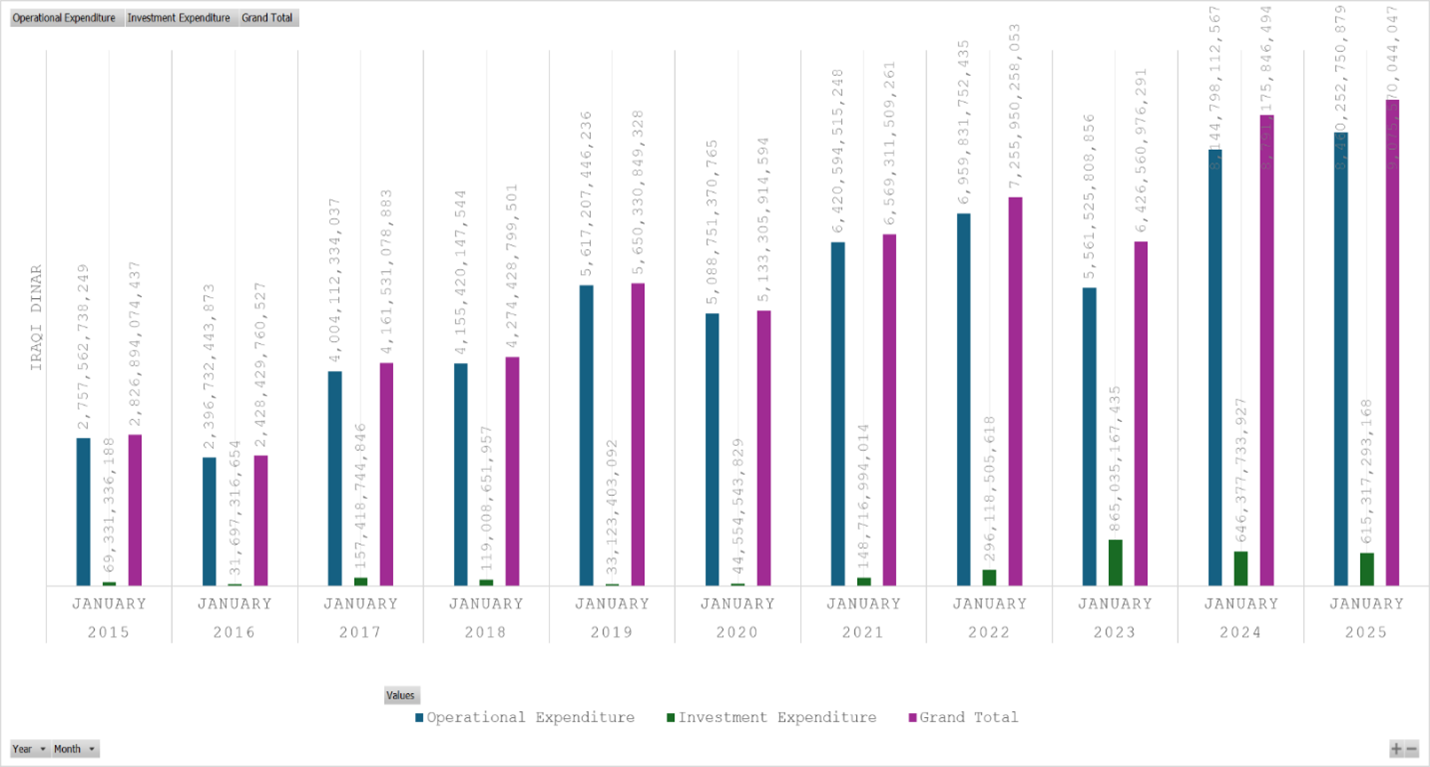

A combination of rising expenditure commitments, the expansion of government functions, the proliferation of public institutions, and the distribution of oil revenues has driven a sharp increase in Iraq’s operational expenditure over the past decade. Operational expenditure rose from approximately 2.75 trillion dinars in January 2015 to 5 trillion dinars in January 2020, before climbing further to 8.46 trillion dinars in January 2025.

A similar upward trajectory is evident in annual aggregate figures. Total public expenditure increased steadily from around 18.5 trillion dinars in 2015 to 76 trillion dinars in 2020, reaching nearly 140 trillion dinars in 2025. Taken together, these figures indicate that Iraq’s total annual expenditure expanded by more than 677 percent over this period.

Graph 1. Total, Investment, and Operational Expenditure, January 2015–2025

Source: Iraq’s Ministry of Finance, Monthly Revenue and Expenditure Dashboard (2015–2025), December 25, 2025; Rudaw Research Center.

Another notable feature of Iraq’s fiscal data is the presence of both sharp increases and, at times, significant reductions in expenditure. Most striking is the demonstrated capacity to curb operational expenditure, including reductions that extend even to public sector salaries. This indicates that expenditure levels are not structurally fixed but can be adjusted when fiscal pressures intensify.

At the same time, the substantial rise in total expenditure has not been directed primarily toward investment, construction, or the development of productive sectors such as agriculture, industry, and tourism. Instead, the increase has been absorbed largely by three categories of public sector outlays: employee salaries, bonuses and allowances, and other recurrent expenses, alongside pensions and social welfare spending across the majority of Iraqi state institutions. Notably, this expansion excludes the Kurdistan Region, which has not been part of this increase.

With regard to the sources of expenditure growth, an examination of combined operational and investment expenditure across the period 2015–2025 reveals that the Ministry of Electricity accounts for the largest increase, with expenditure rising by 15,289 percent. This is followed by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, where expenditure expanded by 5,384 percent, and the Ministry of Industry and Mining, which recorded an increase of 1,960 percent.

Particularly striking is the growth in expenditure by the Council of Ministers, which rose by 635 percent over the same period. In the first month of 2015, expenditure by the Council of Ministers stood at 90.2 billion dinars; a decade later, by the first month of 2025, it had climbed to more than 616 billion dinars.

Another important consideration is that analysis should not focus solely on percentage increases, but also on the absolute size of expenditure increases and the expansion and diversification of expenditure channels. In 2015, operational and investment expenditures were allocated across 32 government institutions in Iraq. By 2020, despite the dissolution and merger of several ministries, this number had risen to 44 institutions and entities. By 2025, it increased further to 47 institutions.

Beyond the establishment of new non-ministerial entities, a major driver of this expansion has been the growing role of governorates, excluding the Kurdistan Region and Kirkuk. These shifts—characterized by recurring processes of reduction, merger, and expansion from one cabinet to another—have made expenditure patterns increasingly complex and difficult to track over time.

For example, in 2015, the Ministry of Municipalities and the Ministry of Construction and Housing operated as separate entities, whereas by 2025, they had been merged. Similarly, the Ministry of Human Rights and the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities, both of which existed in 2015, no longer appear as independent ministries in the 2025 budget structure.

By contrast, 2025 saw the creation of several non-ministerial bodies, including the General Commission for Monitoring the Allocation of Federal Revenues and the Military Industrialization Authority. These entities primarily generate operational expenditures rather than investment expenditures.

The Military Industrialization Authority provides a clear illustration. In the first month of 2025, its total monthly allocation amounted to 12.48 billion Iraqi dinars, of which 12.3 billion dinars were designated for operational expenditure. Nearly 12 billion dinars of this amount were allocated to bonuses, allowances, and other current expenses, while only 161 million dinars were directed toward investment expenditure.

Another important and often overlooked issue is the continued increase in annual expenditure at certain institutions where little substantive change has taken place. In fact, based on the reform agenda discussed during that period, expenditures at these institutions should have declined rather than increased, particularly given repeated commitments to reduce allowances, security details, guards, and other related costs.

The most striking example is the Iraqi Parliament. In January 2015, the Parliament’s total expenditure stood at 36.9 billion Iraqi dinars. By January 2025, however, this figure had risen to 45.3 billion dinars. In practical terms, this represents an increase of roughly 10 billion dinars in monthly operational expenditure, which translates into approximately 120 billion dinars on an annual basis, if not more.

This trend stands in sharp contrast to policy priorities that were widely expected during this period. Agriculture was meant to be strengthened, and basic public services—such as roads, potable water, and sewage infrastructure—were supposed to receive greater investment. Instead, expenditure in key service-oriented ministries declined rather than expanded.

Notably, the Ministry of Agriculture experienced a 25 percent reduction in expenditure, while spending on municipalities fell by 3.8 percent. These declines highlight a clear mismatch between stated reform objectives and actual budgetary outcomes, raising serious questions about expenditure allocation and policy implementation.

A decline in expenditure can also be observed across several institutions over the period under review. Most notably, the expenditure of the Presidency of the Republic of Iraq decreased by approximately 14 percent between 2015 and 2025. In practical terms, this means that while the institution’s total expenditure stood at 3.9 billion dinars in the first month of 2015, it fell to 3.3 billion dinars by the same month in 2025.

A similar pattern is evident with respect to the Kurdistan Region’s expenditure, which appears at the bottom of the chart. This reflects the fact that recorded expenditure during this period was either zero or close to 1 trillion dinars, an amount allocated almost exclusively to salary payments, with little to no allocation for other categories of expenditure.

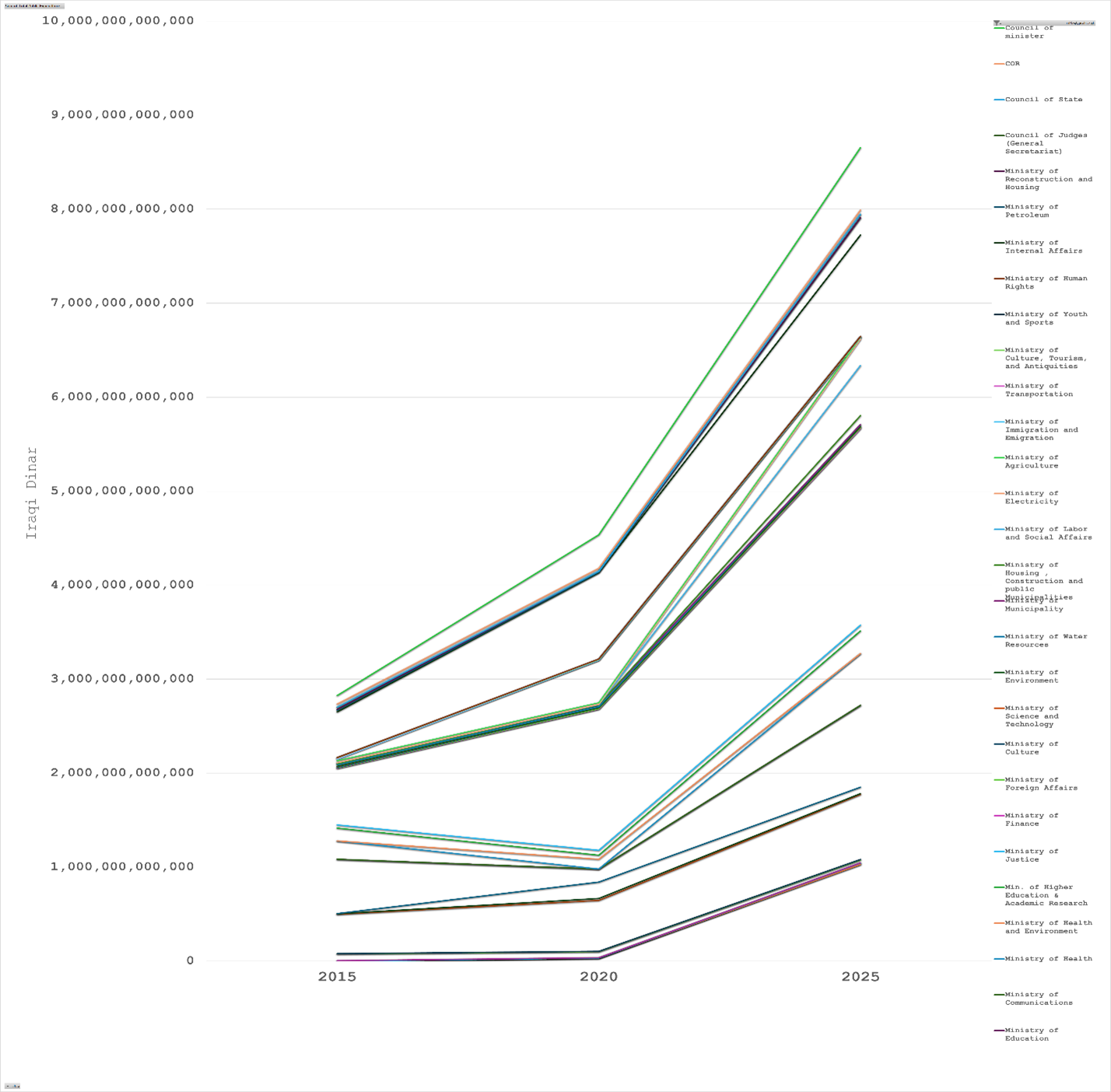

Graph 2. Differences in expenditure across institutions, the three presidencies, and ministries in Iraq, 2015, 2020, and 2025 (first month of each year).

Source: Iraq’s Ministry of Finance, Monthly Revenue and Expenditure Dashboard (2015–2025), December 25, 2025; Rudaw Research Center.

Can Iraq Sustain Its Expenditures in 2026?

According to the latest report issued by the Iraqi Ministry of Finance in November 2025, government expenditure during that month declined by approximately 500 billion dinars, excluding the salaries of employees in the Kurdistan Region.

A closer look at the figures illustrates this dynamic more clearly. Total employee salary expenditure—excluding allowances, pensions, and social welfare payments—stood at 45.56 trillion dinars by the end of September 2025. This figure rose to 51.5 trillion dinars by the end of October and reached 55.9 trillion dinars by the end of November 2025. On a monthly basis, this translates into employee salary expenditures of 5.16 trillion dinars in September, 5.9 trillion dinars in October, and 4.4 trillion dinars in November, excluding the Kurdistan Region.

If the monthly salary expenditure for employees in the Kurdistan Region is conservatively estimated at around 1 trillion dinars, total employee expenditure across Iraq in November would amount to approximately 5.4 trillion dinars. Even under this assumption, the Iraqi state was still able to reduce overall employee expenditure by around 500 billion dinars during that month.

This pattern demonstrates that both increases and reductions in public expenditure remain administratively feasible for the Iraqi state. Adjustments in spending levels—particularly within operational expenditures such as salaries—do not, in themselves, pose an immediate threat to economic stability.

Moreover, this month-to-month fluctuation in expenditure is not an isolated phenomenon but one that can be observed consistently over time. It has not been confined solely to cuts in investment expenditure or other components of operational expenditure. Rather, when fiscal pressure intensifies, even expenditure on public-sector salaries has been reduced, as observed in 2016, 2020, and 2023, as well as in several recent months.

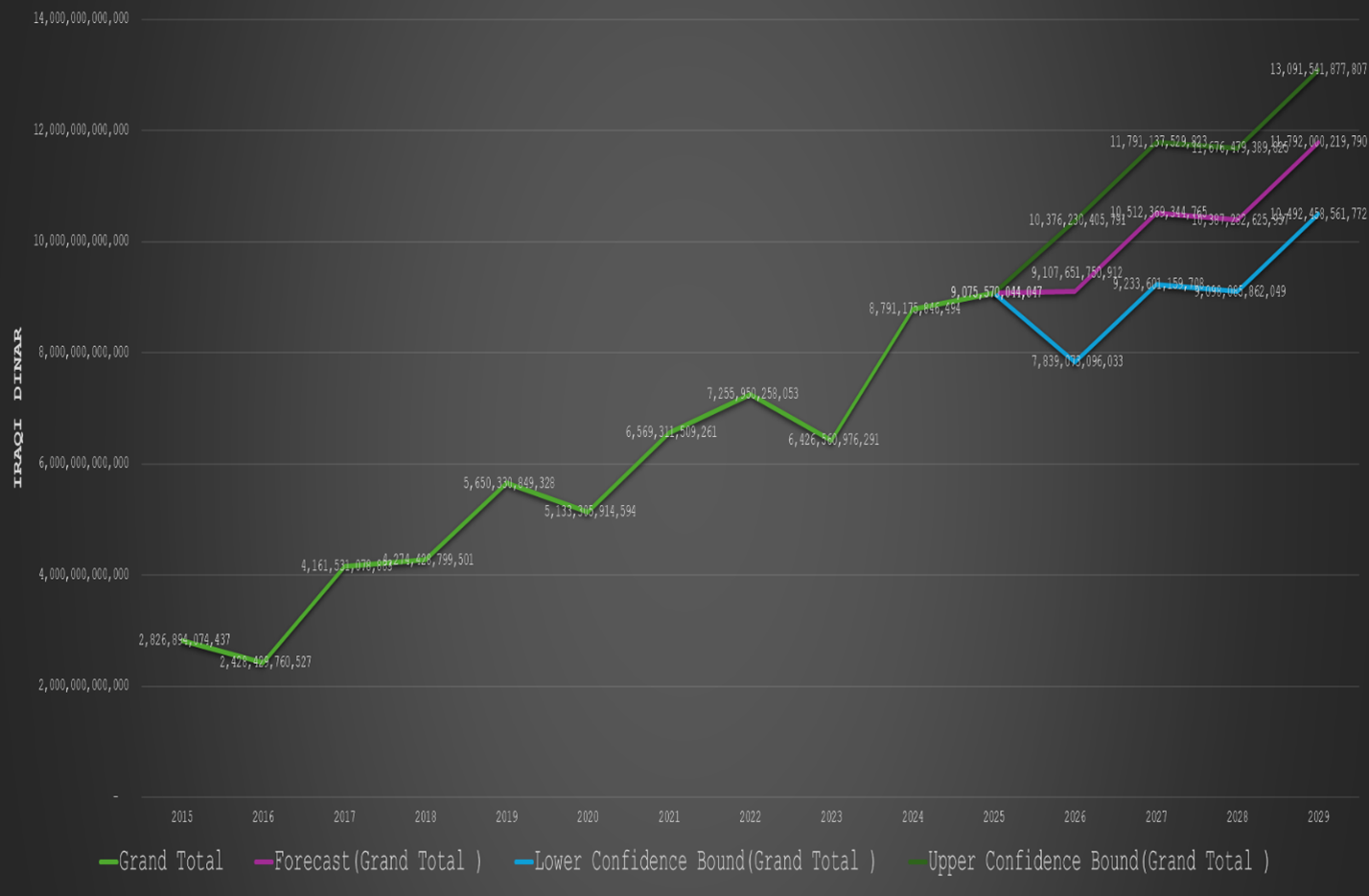

If we project total expenditure for the first month of the upcoming years based on first-month expenditure levels between 2015 and 2025, three potential expenditure paths emerge for Iraq. First, if expenditure is reduced, total expenditure would decline to approximately 7.8 trillion dinars. Second, if expenditure continues along its current trajectory, it would remain broadly stable, with a marginal increase to around 9.1 trillion dinars. Third, if expenditure expands further, total expenditure could rise to roughly 10.3 trillion dinars.

Which of these three scenarios, as illustrated in the accompanying graph, is most likely to materialize depends primarily on oil prices and oil revenues. Despite indications in the final months of last year that a contraction scenario may be emerging, Iraq’s capacity to move toward the second or third scenarios remains constrained. This is because any significant increase in revenue—whether through higher production, greater export volumes, or higher oil prices—lies largely outside Iraq’s direct control.

Graph3. Total Expenditure in January, 2015–2025, with Three Scenarios for 2026–2029

Source: Iraqi Ministry of Finance, Iraq’s Monthly Revenue and Expenditure Dashboard (2015–2025), December 25, 2025; Rudaw Research Center.

Conclusion

The financial data for the period 2015–2025, which captures the total expenditures of all Iraqi ministries and governorates, provides a clear picture of how public expenditure functions in Iraq and how an economy heavily dependent on oil revenues is managed. At its core, this system operates as a mechanism of distribution during periods of revenue abundance and retrenchment when revenues decline.

For this reason, growth in Iraq’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—whether measured at the national level or on a per-capita basis—does not reflect genuine or sustainable economic growth. Public expenditures fluctuate sharply from year to year, and GDP growth follows a similar pattern, as it is not anchored in productive output from manufacturing, industry, or other diversified economic sectors capable of generating exports and long-term income for the country. Instead, economic expansion is driven primarily by government expenditure, particularly salaries, wage-related commitments, and associated fiscal obligations.

It is also important to note that monthly expenditure in Iraq fluctuates significantly over the course of the year, with clear differences between the beginning, middle, and end of each fiscal year. Investment expenditure, in particular, is consistently left to the final months of the year, despite the adoption of a three-year budget framework. In practice, expenditure priorities remain heavily skewed toward salaries, rather than investment, sectoral revitalization, or service provision.

For example, in October 2025, total expenditure exceeded 14 trillion dinars, of which more than 10 trillion dinars were allocated to operational expenditure and around 4 trillion dinars to investment expenditure. This occurred even as the gap between revenues and expenditures continued to widen, underscoring the structural imbalance in Iraq’s fiscal management.

At the same time, Iraq’s monthly expenditure—excluding the Kurdistan Region, investment expenditure, and other categories that could, in principle, be reduced—has fallen to below 8 trillion dinars (approximately USD 6.1 billion). At current conditions, oil exports priced at around USD 60 per barrel are sufficient to cover this level of expenditure. However, this raises a critical question: how long can this situation persist, particularly when oil from the Kurdistan Region continues to be exported, yet not only is the Region’s budget withheld, but even its monthly allocations to cover public-sector salaries remain unpaid?

In general, an economy that retains the ability to adjust its expenditures—both upward and downward—can maintain fiscal sustainability during periods of reduced revenue. In Iraq’s case, however, the pattern of rising and falling operational and investment expenditure reflects a deeper structural issue: significant disparities in expenditure allocation across governorates. These disparities affect not only the Kurdistan Region but also governorates such as Kirkuk.

The following section examines these imbalances in greater detail, focusing on differences in governorate-level operational and investment expenditure between 2015 and 2025.