Overview

In recent days, the Central Bank of Iraq issued a statement seeking to reassure the public regarding the government’s debt situation, emphasizing that there is no significant threat to the economy. According to the Bank, Iraq’s total domestic and external debt amounts to a little over $81 billion.

The Central Bank’s reassurance is based on the fact that, under the three-year budget law, the government was authorized to borrow 191 trillion dinars (approximately $146 billion) to cover the deficit during that period. However, only 35 trillion dinars (about $26.9 billion) have actually been borrowed.

At the same time, the Prime Minister of Iraq stated that “Iraq’s financial and economic conditions are in their best state, with development and reconstruction continuing,” adding that the current debate about external debt arises in an election atmosphere and “is not a technical issue.”

This reassurance from the Central Bank and the Prime Minister of Iraq comes at a time when, a decade and a half ago, Iraq’s external debt stood at $60.9 billion, and its domestic debt was $9.9 billion. By June 31, 2025, however, domestic debt had risen to $67.2 billion, while external debt had declined to $14.45 billion. These shifts and reversals are noteworthy and highlight several important aspects of Iraq’s economy. The key question now is whether the issue of government debt has become part of the election campaign rhetoric or if it represents a genuine threat to the country’s financial and economic stability in the future.

Iraq's Shifting Debt Landscape: Domestic vs. External

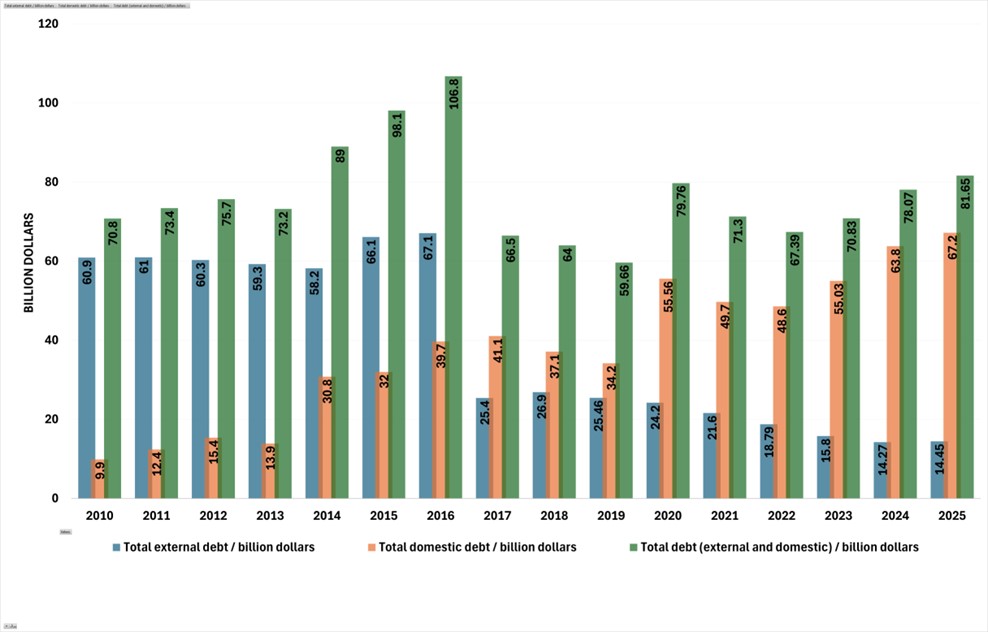

Over the past fifteen years, Iraq’s total debt has increased by approximately $10 billion. In 2010, the total debt stood at $70.8 billion, but by the end of June 2025, it had risen to $81.65 billion.

In reality, based on data from the past fifteen years, despite significant fluctuations in debt levels, two important developments have occurred: first, the overall increase in debt, and second, the reversal between external and domestic debt. In 2010, Iraq’s total external debt amounted to $60.9 billion, whereas by June 2025, it had decreased to $14.45 billion—about $1.5 billion higher than the figure cited by the Prime Minister. In contrast, domestic debt, which was $9.9 billion in 2010, had surged to $67.2 billion by June 2025.

In reality, the repayment of Iraq’s external debts is as closely linked to the post-2003 process as it is independent from the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank of Iraq. For example, in repaying Kuwait’s debt, the U.S. bank where Iraq’s oil revenues are deposited deducted Kuwait’s debt amount per barrel before transferring the remaining funds to the Ministry of Oil. By 2022, Iraq had paid a total of $52.4 billion to Kuwait in debt repayments. This represents an important factor in the reduction of Iraq’s external debt.

Furthermore, between 2016 and 2018, significant changes occurred in Iraq’s debt levels and revenues due to fluctuations in oil income—specifically, the halving of debt and the doubling of oil revenue. In 2016, oil revenues stood at $43 billion, but by 2018, they had nearly doubled to $83.9 billion. These rises and falls in oil revenue directly determine whether Iraq’s debt figures increase or decrease and whether its annual fiscal balance ends in a deficit or a surplus.

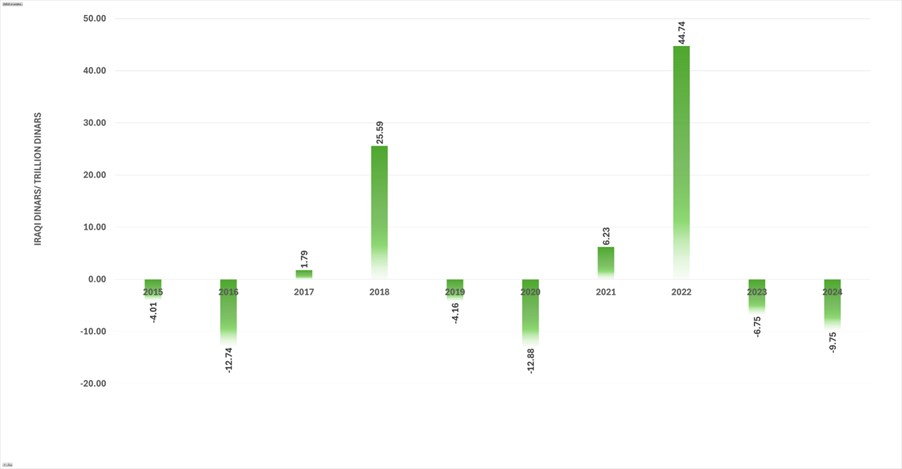

Graphic 01: Deficit and surplus between annual revenue and expenditure in Iraq from 2015 to 2024

Source: Iraq Ministry of Finance, Iraq Budget, Monthly Revenue and Expenditure Report, October 24, 2025

In reality, during the tenure of the current Iraqi cabinet, the country’s total debt has increased by $14.26 billion. However, there has been a reversal in the composition of domestic and external debt: domestic debt has risen by $18 billion, while external debt has decreased by $4 billion.

This shift reveals an important indication, namely, a decline in external confidence in lending to Iraq to finance its economic deficit. It also reflects a further weakening of Iraq’s ability to attract foreign debt for investment and to stimulate growth across various sectors.

Graphic 02: Domestic debt, external debt, and total debt from 2010 to June 2025 / billion dollars

Source: Iraq Ministry of Finance, Iraq Budget, Debt Dashboard, October 21, 2025

When Does Debt Become Dangerous?

During October 8–13, 2025, at the Annual Meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group, one of the main topics discussed was the rising debt of the public sector and governments worldwide, with total global debt reaching 115 trillion dinars. The United States and China together account for half of this amount.

According to the International Monetary Fund, the continuous increase in public sector debt, especially when it exceeds 100% of total GDP growth, creates significant uncertainty and an unclear outlook for national economies. Therefore, now more than ever, it is crucial for countries to implement major budgetary reforms, as they need to build fiscal reserves that will enable them to respond swiftly to major future economic shocks.

Iraq is a unique example in this regard. In its three-year budget, the government has set an annual spending plan of approximately 200 trillion dinars (about 153 billion dollars), while its total oil and non-oil revenues amount to 134 trillion dinars (around 103 billion dollars). This means the three-year budget allows the Iraqi government an annual deficit or debt of nearly 50 billion dollars.

Although the Iraqi government and the Central Bank now claim success in reducing debts by 26 billion dollars during this period, Iraq’s major vulnerability lies in its dependence on oil. This dependence makes the country highly exposed to fluctuations in oil prices or to unexpected events—such as the October 26–27, 2025 incident in Basra, when exports were halted.

Furthermore, the increase in debt and the rise in interest rates have made repayment nearly impossible, leading the overall debt to continue growing. This risk has been a central concern during the annual meetings of both major global financial institutions. Iraq stands as a clear example of this problem, with a bank interest rate of 10%.

In reality, the risk associated with this debt becomes greater and more serious when the borrowing is directed toward covering the needs of the public sector—above all, the payment of salaries, pensions, and financial assistance—rather than being used for investment across various sectors or for transforming the rentier economy. In this regard, Iraq has demonstrated in recent years that the rise in public debt has largely been driven by consumption rather than investment.

For example, the growth of investment expenditure has remained weak compared to that of consumption expenditure. Between 2015 and 2024, investment expenditure increased by only 27%, while total expenditures grew by 54%. In 2015, total expenditure stood at 70 trillion dinars, of which 18.5 trillion dinars were allocated to investment. However, by 2024, when total expenditure rose to 150 trillion dinars, investment expenditure did not even double, reaching only 25 trillion dinars.

Another major risk associated with these domestic debts is their high interest rates, which range between 7% and 10%. The Iraqi government has borrowed these funds from domestic banks, and the debt terms are relatively short. Consequently, the accumulation of such debts means that, in the event of a sharp decline in oil prices, repayment would become impossible—potentially triggering a severe financial crisis and leading to the bankruptcy of both state-owned and private banks in Iraq.

The reversal of debts highlights the weakness of Iraq’s external economic system, particularly in relation to major international banks and their provision of loans. If these debts had not been domestic but rather loans from major international banks, the first condition for granting such loans would have been investment-oriented, with a clear mechanism for repayment within a specified period, rather than allowing debt accumulation. The clearest example of this can be seen in 2016, when Iraq faced a severe security collapse and a sharp decline in oil prices. At that time, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) conditionally provided a $5 billion loan to prevent the country’s economy from collapsing. The conditions included restructuring government expenditures, reducing the annual budget deficit, and increasing spending on investment.

Conclusion

It is true that Iraq possesses 162 tons of gold reserves and 150 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, yet the management of its economy is such that the country remains constantly in debt. Any internal or external shock exposes this weakness, which can be explained by the following points:

First: The ratio of debt to GDP. The Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank estimate Iraq’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 42%. However, since Iraq’s economy depends heavily on oil — with oil revenues accounting for 90% of monthly income — debt analysis should be based on oil revenues rather than total GDP. When calculated this way, the rate exceeds 120%, which is 20% higher than the threshold warned about by the world’s two major economic institutions.

Second: These debts have been borrowed from domestic banks and have not led to increased investment or growth in Iraq’s GDP. Instead, during periods of declining domestic revenues and falling oil prices, the government has resorted to borrowing to cover consumption expenditures. Consequently, current discussions about cash shortages and the government’s reduced ability to meet financial obligations stem directly from this situation.

Third: This reversal between domestic and external debt in terms of amount indicates the contraction and weakening of Iraq’s economy. It reveals that major global banks are unwilling to lend to a country whose consumption expenditure is four times higher than its investment, and whose only significant investments are in oil and gas.

Fourth: Although domestic debt does not pose as much risk to a state as external debt does, it should not be overlooked that domestic borrowing alone cannot make an economy resemble Japan’s; rather, it risks turning it into another Lebanon.

Fifth: Debt should serve the purpose of investment and the expansion of production and profit, not mere accumulation. For example, when Crescent Petroleum and Dana Gas secured a loan of $250 million through the United States to expand the Khor MOR gas project, this borrowing became a productive debt, as it enabled the companies to double their gas production, thereby increasing their revenues. In the first six months of this year, the companies reported a net profit of $73 million; thus, when production doubles, profits will more than double, allowing them to repay the investment debt within a short period. This type of debt is beneficial and does not pose a risk—unlike the case of the Iraqi government, whose total debt is expected to exceed $81 billion by the end of the year, at a time when oil prices are insufficient to cover public expenditures.

Sixth: Iraq’s debt situation is alarming; it is neither an election campaign issue nor a mere technical matter. Instead, it has taken a dangerous turn. If left unresolved, it will drive the economy and the state toward catastrophe.