In late 2025 and early 2026, Iran entered one of the most critical phases in its more than 46-year history since the establishment of the Islamic Republic. A new wave of protests has emerged, spreading to approximately 250 locations across 27 provinces. Although the number of participants appears lower than in previous protest movements, the speed and geographic breadth of their spread, combined with the severe economic pressure faced by ordinary citizens, make this wave particularly significant. However, economic hardship alone does not fully explain the current unrest. Broader structural and political factors are also at play, including declining public trust in the political system during what many perceive as a transitional period, as well as the impact of external political and military developments on Iran’s internal dynamics. The reimposition and tightening of international sanctions, statements by U.S. President Donald Trump regarding the possibility of intervention should protesters be killed, the growing risk of a renewed military confrontation with Israel, and the capture of the Venezuelan President, Nicolás Maduro, have all contributed, directly or indirectly, to shaping the current protest environment.

Iran’s official media has itself described the current unrest as a chain of scattered protests, whose causes are not solely economic, but are rooted primarily in a lack of public trust. It has also emphasized that this movement does not constitute a revolution; rather, it is considered more dangerous than a revolution because it lacks leadership, has no clear horizon, and repeatedly rises and subsides without resolution.

While this assessment largely reflects the viewpoint of Masoud Pezeshkian, the president of Iran, and does not necessarily align with the perspectives of other components of the political and security establishment—some of which continue to attribute the unrest mainly to economic grievances or foreign interference—it nevertheless signals an important shift. From Pezeshkian’s office to the highest levels of Iran’s leadership, the state’s approach toward protesters appears different this time, to the extent that officials are openly speaking of “dialogue” with the dissatisfied. Most likely, this shift is driven by the convergence of Iran’s acute political and economic pressures, alongside mounting internal and external security challenges.

Understanding Iran’s Protests

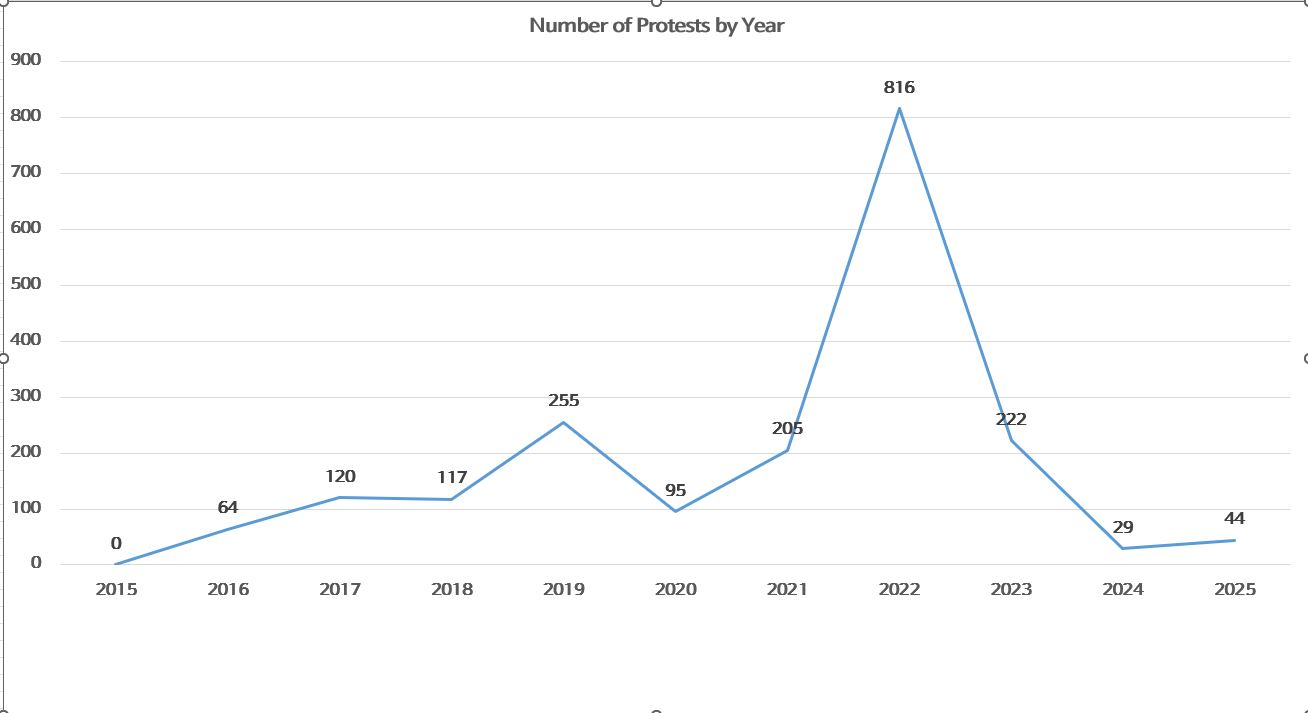

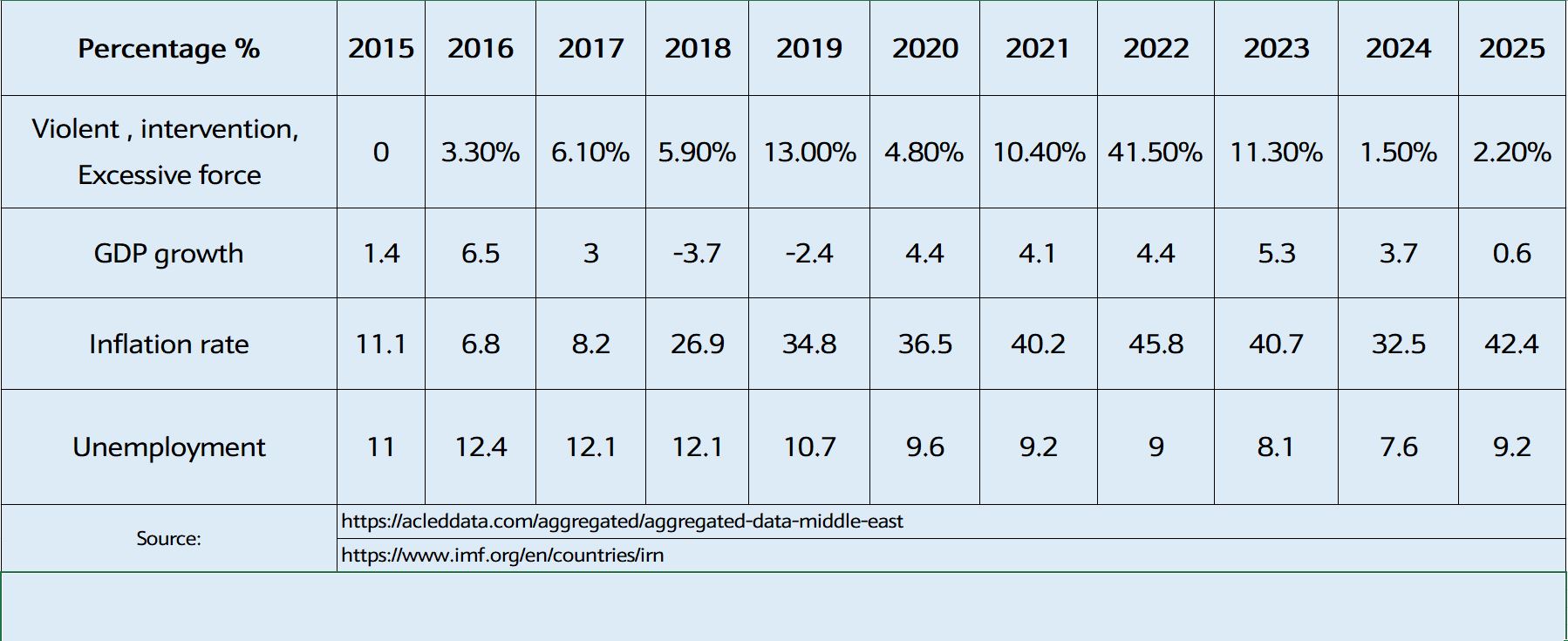

According to ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data), between 2015 and December 12, 2025—a period that does not include the most recent wave that began on December 28, 2025—a total of 30,263 protests, both large and small, have taken place in Iran. Of these, 7 percent were classified as violent protests, in which either protesters or state forces resorted to violence.

It should be noted that the Iranian government regularly organizes annual, peaceful pro-government demonstrations; therefore, not all non-violent protests necessarily reflect public discontent with the state. Protests that clearly fall into this category—those involving violence, arrests, or forcible dispersal by state authorities—number 1,967 cases. According to ACLED’s classification, these incidents involve direct state intervention, often characterized by the use of excessive force, and are categorized as anti-government protest demonstrations.

Taken together, the data indicate that protests in Iran are no longer a temporary or episodic phenomenon, nor are they driven by a single cause. Over time, they have become more violent, more geographically widespread, and increasingly persistent, pointing to a deeper and more structural pattern of unrest.

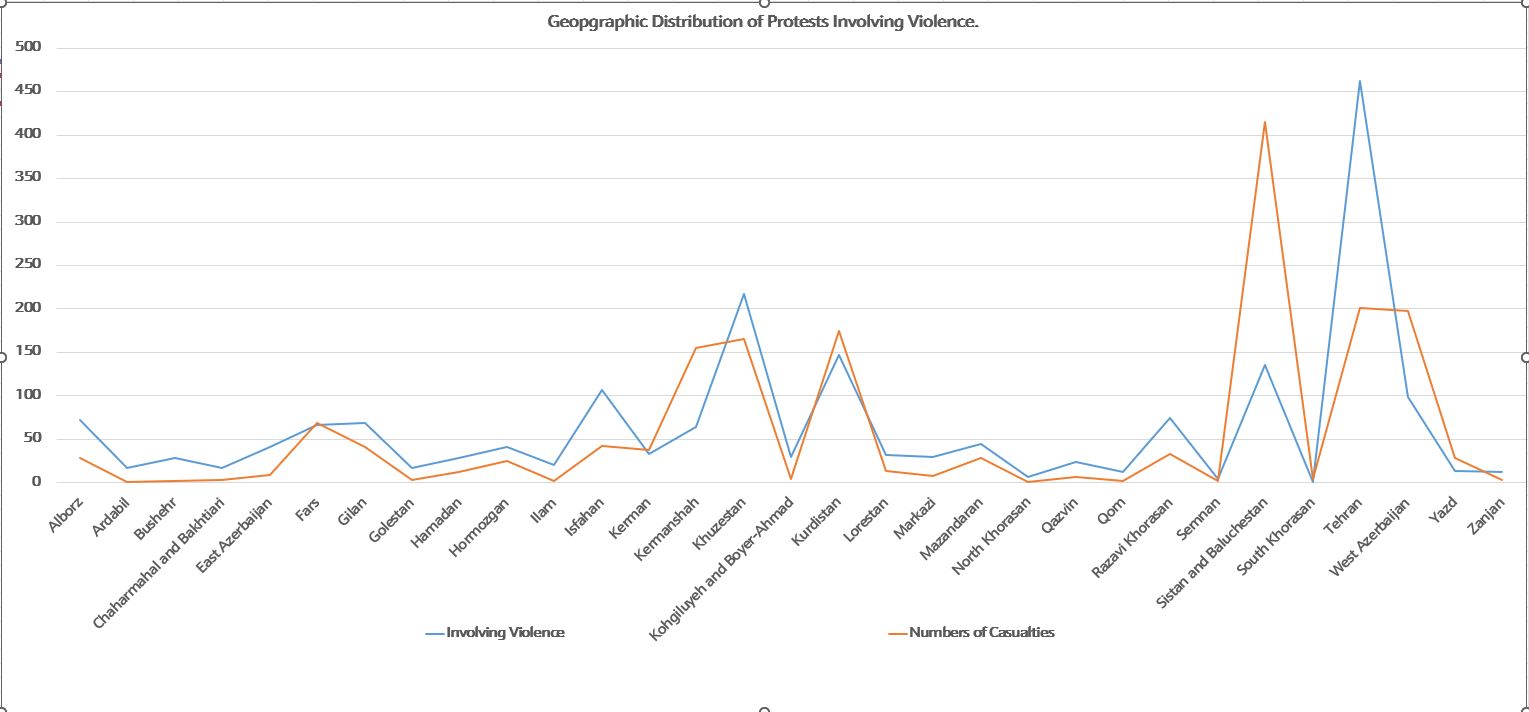

According to available rankings, the highest numbers of anti-government protests have been reported in Tehran (460), Khuzestan (220), Kurdistan (150), Sistan and Balochistan (140), and Isfahan (110). This distribution highlights two key characteristics. First, major Iranian cities such as Tehran and Isfahan exhibit high levels of public discontent. Second, while dissatisfaction has historically been pronounced in Kurdish, Baloch, and Arab regions, it has now spread across nearly the entire geography of the country.

However, casualty figures reveal a clear disparity in the state’s response. The government’s reaction in Kurdish, Arab, and Baloch areas has been significantly harsher than in the central provinces. For instance, in Tehran, with 460 protest events, the number of casualties was around 200. In Isfahan, with approximately 107 protests, casualties stood at 42. By contrast, in Sistan and Balochistan, with around 135 protests, casualties reached 415. In Kurdistan, 147 protests resulted in 175 casualties; in Kermanshah, 64 protests led to 155 casualties; and in Khuzestan, 217 protests resulted in 165 casualties.

This pattern suggests a geographically differentiated state response, in which peripheral and minority-inhabited regions experience disproportionately higher levels of violence. It may also help explain why, in the most recent wave of protests, not all Kurdish and Baloch areas have participated as actively as in previous cycles. At the same time, cities such as Kermanshah and Ilam, where Shiite Kurds form the majority, have witnessed a notable rise in protest activity during this phase.

Another important point is that “persistence” has become a defining characteristic of protests in Iran. With the exception of 2015, when protest activity was largely confined to Tehran and Isfahan, demonstrations since 2016 have occurred across the country, albeit at different scales and intensities.

Historically, major protest episodes have unfolded in waves. In 1999, student protests erupted, and nearly a decade later, following the 2009 presidential election results, larger demonstrations spread to around 40 Iranian cities. From 2016 onward, public discontent has been repeatedly expressed over a range of issues, including inflation and rising living costs, water shortages, fuel price increases, the shooting down of a civilian aircraft by the Iranian military (Ukraine International Airlines Flight PS752), and events related to “Zhina” (Mahsa Amini). In each of these cases, protests that initially emerged in response to specific triggers gradually expanded, taking on broader political, social, and symbolic dimensions as they evolved.

The role of economic hardship in recent protests

Some Iranian media outlets place the unemployment rate at around 7.5 percent, while the IMF estimates suggest it has reached approximately 9 percent. Iran’s labor force consists of about 27.175 million people. At a 7.5 percent unemployment rate, this translates into roughly 2 million unemployed individuals, whereas a rate of 9.2 percent would mean around 2.5 million people without work.

Beyond unemployment, GDP growth stagnation and inflation constitute major structural economic challenges. Among various economic indicators, there is a direct correlation between inflation and protest activity: as inflation rises, the frequency and intensity of protests increase.

Three days before the New Year, the exchange rate reached a new record, with one US dollar exceeding 144,000 Iranian rial (IRR). Shortly thereafter, mobile phone vendors in a shopping mall in Tehran took to the streets in protest, an event that Iranian media describe as the spark of the current protest wave. As the exchange rate surged, official figures announced an annual inflation rate of 42 percent, while point-to-point inflation in December 2025 was announced at 52 percent. This means that the overall cost of goods and services increased by more than half.

Basic necessities were among the hardest hit. Compared to November 2025, prices by the end of the year rose by 26.7 percent for bread, 18.3 percent for eggs, 9.8 percent for milk, and 16 percent for fruit. Such increases impose a crippling burden on large segments of society. Based on these trends, it is estimated that one out of every three Iranians lives below the poverty line.

According to government estimates, an ordinary worker requires at least 50 million Iranian rial (IRR) per month—approximately $350—to maintain a basic standard of living. However, the minimum wage for a married worker in 2025 was set at around $100, highlighting the deep gap between income levels and the cost of living.

According to Iran’s own official data, approximately 26 million people live below the poverty line, among whom 4 million are unable to earn enough to cover even their daily expenses. Income and consumption distribution further illustrate the depth of inequality: the wealthiest 20 percent of society account for more than 46 percent of total expenditures, while the poorest 20 percent account for only 6 percent.

In practical terms, this means that the richest quintile spends 7.6 times more than the poorest. Such an imbalance is a clear indicator of the continued erosion of the middle class and the widening class divide in Iran. Over time, this structural polarization has reduced social mobility and increased economic insecurity, creating fertile ground for persistent protest cycles and deepening distrust between society and the state.

Political dynamics and the protests in Iran

In recent days, a notable number of Iranian political officials have acknowledged that the country’s current economic crisis cannot be attributed solely to the return of international sanctions. President Masoud Pezeshkian has explicitly pointed to poor governance and corruption, stating on several occasions: “If people are dissatisfied, we should not blame America or others—this is our own failure.”

A similar assessment was offered by Abbas Araghchi, Iran’s Foreign Minister, who argued that the roots of the crisis lie not only in sanctions but also in systemic corruption and the shortcomings of domestic management.

At the same time, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, has publicly acknowledged the existence of widespread public discontent and has expressed conditional support for the government’s call for “dialogue” with dissatisfied segments of society. However, he has also emphasized that certain actors seek to incite unrest and must be confronted, reflecting the regime’s continued security-centric approach alongside its rhetorical openness to dialogue.

Beyond public dissatisfaction, Iran’s current political system—long anchored in the dual authority of religious clerics and military elites—is undergoing a quiet but significant transition. Both pillars of the Islamic Republic’s power structure are passing through a period of internal transformation, a development that may itself be contributing to the current wave of protests.

The role of the religious establishment, in particular, has once again become a subject of intense debate, especially in relation to the question of succession to the Supreme Leadership. In practice, the political influence of clerics has become increasingly personalized around the figure of the Supreme Leader and, over time, has structurally declined. In Iran’s first post-revolutionary parliament, Shiite clerics accounted for approximately 52% of all members. Over the subsequent eleven parliamentary terms, this figure followed a steady downward trajectory, falling to around 7% in the most recent election.

A similar pattern is evident in the executive branch. From the first government cabinet through the eighth, clerics consistently made up more than 10% of cabinet ministers. Thereafter, their share declined sharply to around 4%, although under President Masoud Pezeshkian’s current cabinet, clerical representation has risen again to approximately 10%.

Among Iran’s most prominent Shiite religious authorities, there are notable differences in political stances. Ayatollah Naser Makarem Shirazi (98 years old) and Ayatollah Hossein Nouri Hamedani (100) are generally aligned with conservative forces, with Nouri Hamedani having strongly criticized former President Hassan Rouhani’s cabinet. By contrast, Ayatollah Hossein Wahid Khorasani (105) described Rouhani as one of Iran’s most effective presidents, while Ayatollah Asadollah Bayat-Zanjani (84) is considered closer to the reformist camp.

However, beyond the positions of the current generation of Shia cleric authorities, the more pressing question concerns the relationship the new generation of Shiite clerics establishes with politics. In addition to these figures, the political and religious influence of other key actors—such as the descendants of Iran’s previous Supreme Leader (notably Hassan Khomeini), Ali Khomeini (son-in-law of Ayatollah Ali Sistani, based in Najaf, Iraq), the eldest son of the current Supreme Leader, the future role of Hassan Rouhani, and the Larijani family, who hold both political and religious authority within Shiite politics—will significantly shape this transitional phase regarding the role of clerics in Iran’s political system.

Simultaneously, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has maintained a highly active role in Iran’s politics and economy, a role that has expanded significantly over the past decade. For instance, 26 percent of President Pezeshkian’s cabinet ministers have a military background, and the number of military-affiliated parliamentarians has also increased. Prominent figures such as Ali Larijani, Ali Shamkhani, and Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf have actively re-entered politics, reinforcing the military’s influence within state institutions.

At the same time, Iran suffered the loss of more than 30 high-ranking military commanders during the 12-day war with Israel, with their positions subsequently filled by a mix of new appointees and returning senior commanders. In practical terms, these developments represent a redefinition of the military’s role, its interests, and its relationship with the government, with significant implications for the balance of power within Iran’s political system.

Apart from the influence of the military and religious authorities, the positions of ultra-conservatives and reformists remain among the most important factors shaping Iran’s politics. The discord within the political elite of the Islamic Republic is now more pronounced than ever. All three previous Iranian presidents—Mohammad Khatami, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and Hassan Rouhani—and even the current president, Masoud Pezeshkian, have perspectives on governance that often diverge from the conservative wing.

These internal divisions exist alongside external actors seeking political influence. Reza Pahlavi, exiled in the US, the son of Iran’s former Shah, has publicly expressed his intention to play a role in the country’s future, although he currently lacks widespread support. In addition, Kurdish opposition groups are among the most organized, Baluch groups continue to carry out armed operations, and the Azeri population now appears to be the most politically influential minority, with national-Azeri aspirations growing due to their current political and economic leverage.

Taken together, these dynamics indicate that even in the absence of war or widespread protests, significant political change is imminent in Iran, driven by both internal elite conflicts and pressures from organized opposition groups.

Trump and Netanyahu’s impact on Iran’s protests

Beyond the ongoing impact of sanctions on Iran’s economy, U.S. President Donald Trump directly threatened military intervention in Iran if protesters were killed. Shortly thereafter, he arrested Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and brought him to trial, demonstrating once again that his statements should not be dismissed as merely rhetorical.

Iranian officials, including Ali Larijani and Ali Shamkhani, quickly responded, warning that they too could put the lives of American soldiers at risk. Beyond these exchanges and the symbolic or hypothetical implications of Trump’s warning, the fall of Maduro could have wider geopolitical repercussions. Specifically, it may increase the likelihood of another confrontation between Israel and Iran, a development that could profoundly alter the trajectory and dynamics of the ongoing protests in Iran. The fate of Iran’s more than 400 kilograms of enriched uranium remains uncertain, and Tehran’s growing closeness to Russia and China is a source of concern for the United States. For Israel, both Iran’s uranium program and its efforts to restore military parity are potential triggers for conflict.

During the previous 12-day war, one factor that may have prevented the continuation of the war was the potential closure of the Strait of Hormuz, which would have halted energy exports. It is possible that an undeclared understanding or agreement existed: neither Israel nor the U.S. would strike Iran’s naval bases, so Iran would refrain from closing the Strait. This may explain why the Strait was not mentioned during the height of the conflict.

However, in a future conflict, such informal arrangements may not hold. Iran could close the Strait of Hormuz, even if only temporarily. In this context, a Venezuela without Maduro, which boasts around 17 percent of the world’s oil reserves, could play a stabilizing role, potentially helping to mitigate energy market volatility—a factor that Trump could leverage strategically.

Iran’s setbacks in its regional foreign policy—like Assad’s regime fall in Syria; the events of the capture of Maduro in Venezuela, and ongoing conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon—as well as renewed debates over disarming Hezbollah and other Iran-backed groups in Iraq, have diminished Tehran’s influence in its pan-Shia agenda. This shift is increasingly evident in the slogans and rhetoric of recent domestic protests, which now more frequently criticize Iran’s regional interventions and foreign policy rather than focusing solely on domestic grievances.

Conclusion

The intolerable economic conditions, the instability within the political elite, and Tehran’s geopolitical challenges have made the current wave of protests particularly significant for the regime. These protests, emerging from the convergence of multiple political, economic, and security pressures, could potentially pave the way for broader transformations in Iran.

An analysis of protest data suggests that, despite the continuity and scale of protests, particularly in 2019 and 2022, the government has not formally acceded to the demands of protesters. While some policies—such as enforcement of the hijab—were quietly relaxed in 2022, these changes were not codified into official law. The population has increasingly overcome the fear of expressing dissent, yet the government has simultaneously developed mechanisms to control and contain protest activity, retaining significant coercive power. However, external factors—such as the possibility of U.S. intervention under Trump or indirect international support that “softly encourages” protests—could disrupt this cycle, potentially creating openings for significant political or social change.