Topics

Introduction

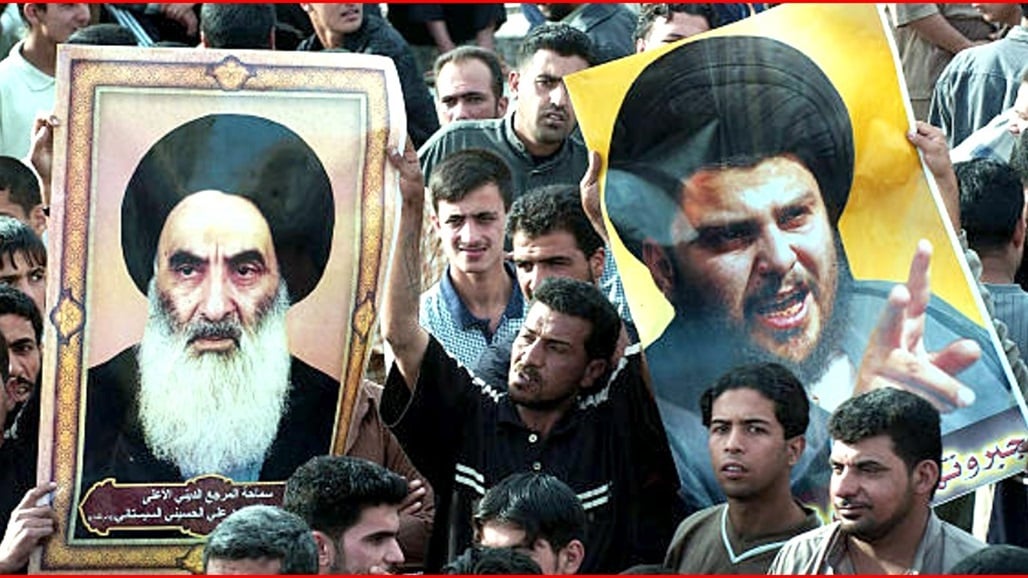

Over the past two decades, Iraq has witnessed open and hidden competition and a power struggle between Shiite forces in the post-2003 political system. The conflict, which manifested in tensions, clashes, and changes in alliances, had a direct impact on Iraq's political and security situation. Tensions have steadily risen over the last two decades. The conflict has spilt over from the siege of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani's residence in 2003 (Al-Qarawee, 2018) to the recent clashes between supporters of the Sadrist movement and the coordination framework in 2022 (Davison and Kadhim, 2022). Since Shiites are the dominant force in Iraqi politics, it is crucial to understand the nature of their struggles. Nevertheless, internal Shiite tensions could affect Baghdad's relations with the Kurdistan Region, the Sunni situation, and even the operations of the international coalition against ISIS and the United States politics in Iraq. Therefore, it is a security issue as much as an internal political issue.

Two critical events in the last four decades paved the way for the rise of political Shiism. The first was the Iranian revolution in 1979, at the peak of the Cold War. The second was the Iraq War in 2003, when the U.S. was at the height of its power and abilities worldwide. Now that the world order is about to change, China has emerged as a strong competitor to the United States. Many regional powers, such as Russia, North Korea, and Iran, are creating obstacles to the US-led world order. The desire of the United States to focus more on great power struggles and have less interest in the Middle East have paved the way for the formation of new alliances and an arms race in the foreign policy of many Middle Eastern countries over the past decade, such as the Abrahamic Agreement, the rapprochement of the Gulf states with China and Russia, and the 25-year agreement between Iran and China.

The main driver of foreign policy behaviour is protecting the political system, which may have become a higher priority for regional officials due to the changing world order. However, another dimension of the transformation in the region is the local situation, which changes due to many factors, such as advances in communication technology, population growth, etc. Unlike the Cold War, when ideology and religion dominated Middle Eastern politics with charismatic leaders, today, ideologies are less critical than before, and conflicts among the ruling elite in many parts of the region have emerged.

Along with the general changes in the world and the region, Shiite politics in Iraq and the area are in turmoil. In recent years, especially since 2018, there has been a strong wave of widespread protests against the Shiite authorities in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon. Moreover, the infighting of the Shiite ruling elite has become a prominent feature of regional politics. Power struggles are the most critical internal Shiite conflict in the Middle East. In the last two decades, reformists and conservatives have been vying for power, and the power struggle between the Sadrist movement and other Shiite groups reached its peak in 2022.

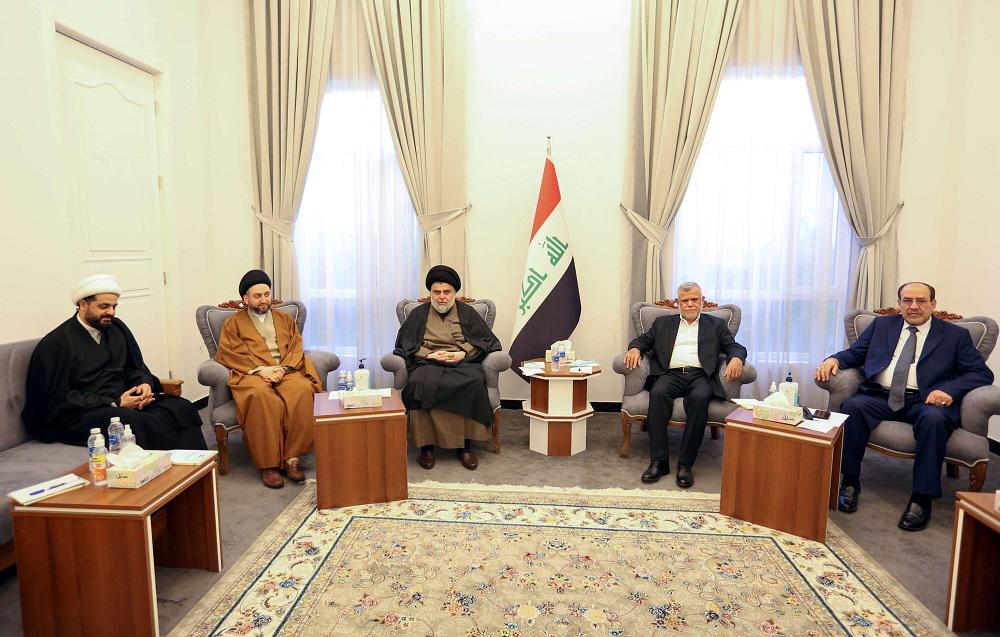

The rivalry between Najaf and Qom seminaries, al-Sadr's rivalry with other Shiite groups, like the followers of Ayatollah Sistani, and pro-Iranian groups that accept Khamenei as a reference, and Ammar al-Hakim's efforts to revive his family's status are among the most critical internal Shiite rivalries. At the same time, the struggle between the Shiite forces over the division of political power, as happened after the October 2021 elections, and the rise to the level of armed conflict have become an essential part of the Iraqi political scene.

Apart from the direct and indirect competition between the two poles of Qom and Najaf seminaries, their power level also affected the internal conflict between the Shiites. Until 2018, Ayatollah Sistani played a decisive role in Iraq. However, after 2018, Sistani was no longer a decisive factor until the conflict between al-Sadr and the Shiite coordination framework reached the level of armed conflict. Moreover, despite not hearing his pleas that the demonstrations should remain peaceful (Reuters, October 25, 2019) and not kill the protesters (English Arabic, October 10, 2019). Likewise, the role of the Iranian leader in Iraq decreased, especially after the killing of Qassim Sulaimani. Iran's inability to persuade al-Sadr to have an agreement with the Shia coordination framework was one of the indicators for that. However, al-Sadr eventually gave the green light to form a government. The 2022 demonstrations in Iran may have been an influential factor in that al-Sadr's permission. Because al-Sadr, after all, belongs to the same intellectual movement in Shiism that directly calls on clerics to intervene in politics, even if he thinks differently from Iranian officials. The collapse of the Iranian clergy system could also reduce the role of the Shiite clerics in the region, which is the last thing the young cleric wants, even if he sees the overwhelming power of the Iranian clergy in Iraq as a threat to himself.

Literature Review

Both the principles of "imamate" and "occultation" are potent sources of political Shiism (Kalantari, 2019). The belief that an Islamic community needs a "mujtahid" to explain religious principles is that someone should lead society on religious grounds. In the sect of the Twelver Shia Imam, which is the most widespread among the Shia in the world, there is another belief that the Twelfth Imam, who is in the "unseen" period, will one day dominate the Islamic system in the world, and until that day mujtahids will lead the people. In the Najaf seminary, these ideas have developed in the form of the supreme reference, and in Iran and the seminary of Qom, the concept of jurisdiction is supported. Qom and Najaf share something in common about spreading Shiism around the world. Qom considers "exporting the revolution" abroad within religious universities, religious representation, and political and military efforts. The Najaf seminary does this more peacefully and within the framework of the seminary covered by the Marja model.

In general, there are three different views on the relationship between the Shiite religious elite and politics. The first point of view examines the relationship between Shia religious elites and politics as a dichotomy of quietism and activism (Nakash, 2003). This view believes that some Shia religious elites, especially in Najaf seminary, such as Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei and Ayatollah Ali Sistani, do not want to interfere in politics and are "quietists." On the other hand, another movement that does not want to remain silent is known as "activists," such as Mohammad Baqir Sadr, Khomeini, and the current leader of Iran, who emphasize the need for direct interference in politics and governance. In this regard, Qom seminary in Iran defends the theory of the jurisprudential state (Kalantari, 2019). The second view emphasizes the limited involvement of the Shiite religious elite in politics.

In contrast, the third view rejects the dichotomy of quietism and activism, believing that the clerics have interfered in politics whenever the opportunity has arisen. Given the historical and practical experience of more than two decades in Iraq, this view holds that even Ayatollah Sistani was inclined to interfere in politics (Fuller, Francke, 2000). Ayatollah Sistani has played an important role in Iraqi politics, including drafting the constitution, approving prime ministers, and many other issues (Mamouri and Khalaji, 2019 ).

In general, three main perspectives can be discussed to explain the role of political elites in countries with conflicts and tensions. One tries to explain the conflicts between countries' elites based on the "political opportunity" argument. On the other hand, this argument believes in the dynamic nature of the position of the elite. It emphasizes that during times of change, when opportunities for replacing the ruling elite arises, the possibility of elite clashes increases (Carboni, 2020). The second point of view explains inter-elite conflict through the state's capacity (Fearon, Laitin, 2003). It means more conflict and clashes between political elites will occur whenever the political regime changes or weakens. However, this view, which gives the state a central role, has been criticized for being incompatible with the state-building process in the Middle East because the boundaries between formal and informal power are not very clear in the Middle East. Many different circles of elites influence power and politics. While the classical view of the ruling elite describes it as a homogeneous and autonomous class created by bureaucracy and the division of labour, other views reject the homogeneity and internal unity of the elite (Carboni, 2020). Volker Perthes defines political elites as those who make or help to make strategic decisions at the national level (Perthes, 2004:5). If participation in the strategic decisions at the national level is the criteria for elites, in that case, the religious elites in the Middle East are political. At least in countries such as Iraq and Iran, it can be political because some religious elites have an active role in political decision-making at the national level. The third view emphasizes religion's role in causing tensions and tension-related conflicts. Also, September 11, 2001, events brought attention to the role of "religion" and "ideology" in international relations and security issues (Thomas, S. 2005).

In Iraq's example, the emergence of ISIS and the influence of Shiite militias on Iraqi politics are examples of the influence of religion on domestic and foreign policy.

"Religion can reduce or increase conflict, influence society's values and international institutions, and even influence foreign policy. Historically, religion has played an essential role in many political rivalries and conflicts worldwide. In the West, this role was reduced with the advent of the Westphalian state system and the emergence of the New Modern State due to two crucial processes: modernization and secularization."

Haynes, J. 2021

Nevertheless, the prediction that societies change to a more complex culture through secularization and institutional formalization has not come true in the Middle East (Hasan, 2018).

For sure, religion impacts politics not only in the Middle East but also around the globe as a whole. Religion can play a role in reducing conflict. However, it can also play a role in increasing tension and conflict, especially when it becomes part of the understanding of the conflict (De Juan, 2014). De Juan links the role of religion in tensions and conflicts with the ability of the religious elite to mobilize the masses, emphasizing that people support violent acts not only for objective reasons of protest but also for understanding and ways of thinking (De Juan, 2014). Identity, ideas, and religious organization are the three main dimensions of religion (Haynes, J. 2021), which can be affected by religious elites. Religious elites seek to increase their influence or power because they believe their religious views are correct or for personal gain (Nancy, 2003). Many examples of violence in the Middle East show how a particular spiritual understanding has paved the way for violence. However, the personal interests of the elite are an essential issue concerning the influence of the Marja.

One point of view links the internal struggle of the Shiite elite in Iraq to three factors: the weakness of the Shiite leadership, the gradual removal of a common enemy such as ISIS, and Iran's desire to divide the country's Shiites for its interest (Veen, Grinstead, and El Kamouni-Janssen, 2017). Regarding the influence of the Marja on Iraqi politics, Mamouri and Khilji mentioned the internal Shiite rivalry, especially between the seminaries of Qom and Najaf. Both believe that, after Sistani, Iran will be more empowered to dominate Iraqi Shia religious-politic sense. There are additional studies on the influence of Ayatollah Sistani on the Iraqi political process, and there is also much research on Iran's power and influence in Iraqi politics. Kjetil Selvik and Iman Amirtemur highlight the obstacles posed by Muqtada al-Sadr to Sistani and Iran from the perspective of the "big man" theory (Kjetil & Iman, 2020). Benjamin Ishkhan and Peter E. Mulherin also discussed internal Shiite rivalry and the role of the al-Hakim family through a discussion of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (Benjamin & Peter, 2018). This article also examines the nature of the Shiite conflict within Iraq and discusses its different parts.

Theoretical Framework

From the perspective of the "regional security complex theory," the internal Shiite conflict is inseparable from the sweeping change that is taking place in the global and regional order. The Cold War and subsequent U.S. hegemony increased political Shiism development due to the Iranian revolution in 1979 and the Iraq war in 2003. The world is in transition, and the regional system is changing, directly impacting Middle Eastern politics, including Shiite politics.

Meanwhile, "Power Shift," written by Joseph Nye, discusses the increasing role of non-state actors in politics and international relations (Wang, Nye, 2022). It may open the door to understanding the role of the religious elite in Middle Eastern politics. Religion can constitute a state actor, and the religious elites, as in the case of Iran in the form of presidents and government officials, can generally play a formal role. Religious elites can participate in politics in three ways as non-state actors: "individuals, movements, and institutions" (Haynes, J. 2021). Phrases like "para-statehood" and "informal sovereignty" (Hasan, 2018) can suggest that state-building is not the same everywhere in the world as it was in the West. Such as Ayatollah Sistani's political role in Iraq, where he does not have a formal position as a politician.

The Shiite tradition is based on the leadership of exemplary people who derive their legitimacy from piety and knowledge. This belief paves the way for the embodiment of the role of the individual in Shiism (Kalantari, 2019). Therefore, the theory of the "big man," whose power comes from a social position, can be helpful here (Selvik & Amirteimour, 2020). Religious elites can influence tensions and conflicts by explaining the religion's established tenets to the public and their supporters. However, this can be done in two ways: by increasing or decreasing friction (De Juan, 2015). In Iraqi Shiite politics, the role of Ayatollah Sistani, Khamenei, Sadr and Hakim families appears to be mainly on the horizon. There are three main types of religious authority in Iraq: self-building authority (based on personal opportunities, e.g., Sistani), state-building religious authority (such as Khamenei), and hereditary religious authority (Sadr and Hakim).

Attempts to increase influence and power are among the leading causes of conflict and internal Shiite tensions in Iraq. Many historical facts and examples prove that differences in religious opinions and interests led to these conflicts. The battle is not limited to spiritual issues, as all significant Shiite religious actors, including Ayatollah Sistani, are politically, militarily, and economically active.

This article emphasizes the role of the individual, the religious authority, in the internal Shiite tensions in Iraq. Several political and social factors may affect the increase in internal Shiite tensions; however, the most critical and decisive factor relates to Marja's rivalry because the Shia religious authority is in a crucial position to influence significant political, economic and social events. Many previous studies emphasized competition for increasing power and influence as a significant factor in the conflict. This essay hypothesizes that the supreme marja's weakness, especially after 2018, is the main reason for the increase in internal Shiite tensions.

The Shiite Elite and Hegemonic Competition

After the fall of the Baath regime, the competition between the various Shiite groups for leadership took an ideological and political dimension as well as a security and military one. Almost all major Shiite groups have armed forces, and this dimension of internal Shiite rivalry has intensified since the war against ISIS. Dozens of armed groups have organized themselves under different names called the Popular Mobilization Forces, which are divided into three main groups: the threshold (Aatabat) crowd of Sistani, the loyalist crowd (walaey), and the Peace Brigades affiliated with al-Sadr. Since the factor of using force and armed capabilities, along with political and ideological efforts to increase power and influence, has also developed in the internal Shiite rivalry, we can call this rivalry dominant. In general, from the first period after the fall of the Baath regime until 2018, despite the strong internal competition, the armed struggle between Shiite groups was more external. The Mahdi Army's role in the sectarian war in Iraq based on fighting Wahhabism, fighting ISIS, and anti-American rhetoric was popular with most Shiite groups.

Sadr and groups close to Iran considered the United States an invader, and even Ayatollah Sistani did not meet directly with American officials for the same reason. The difference was in the behavior of the Hakim family. The Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution, which was under the rule of Al-Hakim, reorganized itself after returning from Iran in the year following the revolution and became the Supreme Islamic Council of Iraq. Al-Hakim himself visited the United States and emerged as a federal advocate for southern Iraq, trying to present a different point of view than other Shiites. All actions of Shiite actors, whatever the external reason, may be accompanied by a strong dimension of internal competition.

Al-Hakim's family approached Sistani, who was appointed by the Islamic Supreme Council as its reference in 2007. This came one year right away after it was established in Iran. In contrast, Sadr's relationship with Sistani was not good. Hakim's behavior sparked growing anger among pro-Iranian groups and individuals within the Islamic Supreme Council.

Badr, the military wing of the Supreme Islamic Council, unofficially broke away from the organization in 2007 and moved closer to Nouri al-Maliki, who had the support of Muqtada al-Sadr. In 2009, Abdul Aziz al-Hakim died of cancer. Overmore, later, the disappearance of Ayatollah Muhsin al-Hakim's son sparked tensions between some leaders of the Supreme Islamic Council and Ammar al-Hakim. The struggle continued until Ammar al-Hakim defected and al-Hikma movement was formed.

Al-Hakim then ran in 2021 with Haider al-Abadi, who led a dissident wing of Maliki's Dawa Party, on a joint list. Both were seeking to develop more relations with Arab countries and the outside world. However, the election results of the Hakim-Abadi coalition, which won only four seats, threatened to erase him from Iraqi politics. In addition, the strengthening of Muqtada al-Sadr, who changed his policy of approaching pro-Iranian groups in 2018 and shifted to developing closer ties with protesters and Ayatollah Sistani, was another threat to the role of the al-Hakim family. in Iraqi politics. Therefore, Ammar al-Hakim participated in the Shiite coordination framework competing with al-Sadr.

Even though he said he would not participate in the new government. Pro-Iranian groups have highlighted the religious role of the Hakim family against Sadr by holding religious ceremonies at al-Hakim's residence. This was as much a religious celebration as it was a sign of a shifting alliance and strong internal Shiite rivalry.

After 2003, there were several reports of the siege of Ayatollah Sistani's house in Najaf by supporters of the Sadrist movement, which were later denied. However, after the death in 1992 of Ayatollah Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, who criticized the tradition of involving clerics in politics championed by Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr and al-Sadr II, al-Sistani gained a powerful position in the Shiite world. It was a rare example of obtaining written permission from Ayatollah al-Khoei to lead the imamate, so it was difficult for al-Sadr to erase him from Iraqi politics, especially since he was internationally accepted. In 2003, Abd al-Majid Khoi, the son of Ayatollah Khoi, was assassinated in Najaf, but Sistani increasingly became the most powerful political figure in Iraq, while Muqtada al-Sadr whose father was executed by the previous regime wanted to have a greater role.

As much as Sadr’s declaration of war on Wahhabism was a rivalry between Sunnis and Shiites, it was a rivalry with Sistani and Hakim, who had gained a powerful religious and political position. Al-Sadr wanted to appear as a hero defending the Shiites and against the "occupier". Despite strong ties to Iran, al-Sadr also encouraged nationalist rhetoric. Part of this may have to do with his rivalry with Sistani and Hakim. Most of the top Iraqi authorities in recent history were of Iranian origin. So keeping nationalist sentiments alive could be beneficial to Sadr in the intra-Shia rivalry. Even when Ayatollah Kadhem al-Haeri criticized al-Sadr and called on his supporters to accept Khamenei's marja', al-Sadr insisted that Najaf is the marja'. However, Sadr did not mention Sistani's name as the marja in Najaf. Especially after 2018, when Sadr broke with pro-Iranian groups, al-Sadr used the Iraqi nationalism as a powerful tool against Iran and its puppets. In recent years, al-Sadr has repeatedly referred to "resistance groups" as "contract" groups, stating that they work for Iran and oppose Iranian interference in Iraq.

There is no doubt that Ali al-Sistani, the supreme authority of Najaf Seminary, and Iranian leader Ali Khamenei are among the most influential Shiite religious and political leaders. The indirect competition between the two is considered one of the most critical internal Shiite conflicts with three dimensions: religious-political, security, and economical. First, al-Sistani disagreed with the Islamic Republic's system of Wilayat al-Faqih. He was a student of Ayatollah Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, who thought the state of the clerics was heresy. Contrary to the Iranian Islamic Republic's system, Sistani belongs to a Shiite intellectual movement that considers power to be the right of prophets and imams only (Mamouri and Khalaji, 2019). A dispute between the two sides is about which side can control Shiite institutions. Religious schools and the administration of holy shrines (Atabat) are among Iraq's most influential Shiite religious institutions. The (Atabat) Administration is state-owned and, like the Imam Reza Shrine in Mashhad in Iran, has several companies and institutions (Al-Qarawee, 2018). In 2022, after Sudan came to power as prime minister, the Hashdi Shaabi established a company called Mohandis, which is likely to become part of the economic rivalry between Khamenei and Sistani in Iraq due to the dominance of pro-Iranian groups in the PMF.

Like Iran, which has strengthened its armed groups since the war against ISIS (Michael and Hamdi, 2020), the administration of the four Shiite shrines has set up four brigades. Despite allegations of joining the Iraqi security forces, the (Ataba) parties still had their organization even after the ISIS war, and they ran a conference for them. One of the reasons for keeping Hashd al-Atabat is that groups close to Iran did not merge their forces with state institutions and wanted to remain as a parallel institution of the Iraqi army and police, like the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. It prompted Hashd al-Atabati to maintain its military establishment like its rivals.

Because of the donations made by pilgrims in the form of "zakat and fifths," as well as the subsidies it receives from the state as an official institution enacted in 2005 (Al-Qarawee, 2018), the shrines are an essential economic, religious, political, and military institution that exerts an influence on internal Shiite rivalries. However, the appointment of any director of shrines requires the approval of Ayatollah Sistani, the supreme authority in Najaf. Nevertheless, control of the state and government institutions could also allow Sistani's rival groups to have a say in these religious institutions. Since 2003, Khamenei has set up at least 100 independent religious schools in Iraq. These schools have representatives in holy places like Najaf, Karbala, Samarra, and Kadhemia (Khalaji, 2016). Ayatollah Sistani also has 600 representatives all over Iraq and offices in Qom and Lebanon (Mamouri and Khalaji, 2019).

Al-Sistani met with political figures such as Rafsanjani (Iraqinews, 2009) and Rouhani (Farda, 2019), but he "refrained from meeting" conservative Iranian officials such as Ahmadinejad, Shahroudi, and Ibrahim Raisi, who are close to Khamenei or were close to him, and visited Iraq at that time. In 1994, the imam of Friday prayers in Tehran, Ahmad Jannati, described Sistani as an employee of the U.K. In 2004, Sistani went to Lebanon upon his return from a British medical trip, but he did not allow Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah to receive him (Al-Mamouri, 2019).

Despite the rivalry between Sistani and Khamenei, after the fall of the Ba'ath regime, Iran adopted a policy of compromise with Sistani, perhaps for political reasons. Iran's concerns about a possible attack or pressure from the USA were essential in preventing Khamenei from becoming a solid rival to Sistani in the early post-Saddam years. However, due to his influence in the Shia communities, it is hard for Iran to be against Sistani publicly. After the war against ISIS, Iran's primary strategy to influence Shiite politics took on a security dimension, as former Quds Force commander Qassim Soleimani emerged as the leading figure in Iranian politics in Iraq. For this reason, the Shiite armed forces and the "resistance" groups were increasing then. One reason for putting more attention on security was because of the inability of Iran to dominate the Najaf seminary and religious authority in Iraq. So, explaining the Inra-Shia tensions in Iraq through inter-elite power struggle may not give the whole picture of Intra- Shia tensions. It leads us to the other factor, which will be discussed below; the weakness of the Marjayiat.

The weakness of the Marjayiat and internal Shiite tensions

Since 2018, signs of the weakness of the Shiite religious authority have become more evident after Ali al-Sistani, and Ali Khamenei lived a golden age of power. Factors such as the emergence of internal discontent and increased internal rivalries among the ruling elite were the main reasons for this weakness. Until 2018, Ayatollah Sistani was a decisive factor in the appointment of Iraqi prime ministers. He prevented al-Maliki's third term and even formed a joint Shiite electoral list, as he did in 2005 (Al-Qarawee, 2018). Nevertheless, Sistani did not play that role in appointing Kadhemi and Al-Sudani. Although he was repeatedly asked to mediate amid al-Sadr's struggle with the Shia coordination framework (Shafaq, 2022), he did not intervene until the threat of a military conflict between the two sides increased in August 2022. He had already discovered that he was not being listened to as often as he used to be. In 2018, he called on people to vote. However, in the 2018 and 2021 elections, less than 40% of people participated, especially in the southern provinces of Iraq. He had called for peace during the October 2019 demonstrations and not to kill the demonstrators. However, neither the demonstrators nor the government listened to Sistani's demands. The October 2019 demonstrations were against the political system, which Sistani had played a significant role in the establishment of it. The strengthening of al-Sadr's standing in both the 2018 and 2021 elections, the strengthening of groups close to Iran, and Tehran's desire to exert a more significant influence in Iraq have weakened Sistani's power.

Since 2009, like Sistani, Ali Khamenei's authority has faced significant obstacles in Iran. First, the barriers of the reformist wing, and then the blocks put in place by conservatives such as Rafsanjani, Rouhani, and even Ahmadinejad, took the disputes among the ruling elite in Iran to another stage. As with the October 2019 protests in Iraq, there have been anti-government demonstrations in Iran every year for the past five years (Rojhelati,10; 2022). Despite its internal weaknesses, one of the main reasons for Iran's weakness in Iraq was the demonstrations in October that expressed an anti-Iranian viewpoint later developed by Muqtada al-Sadr. Burning its consulates in southern Iraq indicated anti-Iranian sentiment in Iraq (BBC, 2019).

After 2018, the desire of the Arab and Gulf countries to play a more significant role in Iraq, the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear agreement, and the new U.S. sanctions have reduced Iran's economic opportunities and its ability to conduct regional activities. Iran, which has funded Shiite groups for years, needed Iraq as a market and outlet to avoid the U.S. sanctions, and this reduced the country's influence in Iraq. For example, perhaps Iran's long silence on Sadr's rivalry with the Shia coordination framework or maintaining relations with Kadhemi, despite the dissatisfaction of his supporters, stemmed from an economic need that could not have been met without the government's and Sadr's approval.

For example, the Kadhemi government facilitated deals to buy natural gas and electricity or pay off Iranian debts (INA, 2022). On the other hand, the killing of Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis was influential in undermining Khamenei's hegemony over Iraq. Even though the new leader of the Quds Force went to Iraq several times in 2022, he did not get Moqtada al-Sadr to agree to form a government with the Shia coordination framework. Even Ayatollah Kadhemi al-Haeri's resignation letter, in which he harshly criticized al-Sadr, did not convince him. Haeri was the Marja of the Sadrist group selected by the second Sadr. He asked Sadrists to follow Khamenei as their Marja, and al-Sadr refused. However, Sistani's message after the tensions in August that reforms could not be implemented outside the government (Rojhelati, 8; 2022), along with Zhina Amini's protests in Iran, were two important reasons for Sadr to allow the Shia coordination framework for government formation. The Sadr family has long supported the clergy political system, and the possibility of the fall of the Islamic government through demonstrations in Iran could also affect Iraq. Therefore, after the demonstrations expanded, al-Sadr's supporters on social media stopped supporting the demonstrators in Iran, and al-Sadr himself warned of the growth of anti-clerical movements in Iran.

Another reason for the weakness of Khamenei and Sistani is the issue of age and health, which has become increasingly debated in recent years. Khamenei is 83 years old (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022), and his illness has been reported several times in the media. Sistani is 92 years old (Biography, the Official Website Sistani), and replacing both has been on the agenda for several years. Competition for power is regular, and the Iraqi Shiites, the country's most significant component and making up 60% of the population (Department of State, 2019), have had the opportunity to increase their power since 2003. However, the intra-Shia competition for power increased during this period. In the two decades since the fall of the Ba'ath regime, there have been at least five significant divisions among the three main Shiite political parties in Iraq: the Dawa Party, the Supreme Islamic Council, and the Sadrist movement.

| Year | Party | Maverick |

| 2006 | Sadr-Mahdi Army | Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq - Khazali |

| 2007 till final isolation (2012) | Supreme Islamic Council of Iraq | Badr Organization - Amiri |

| 2008 | Dawa Party | National Reform - Jafari |

| 2017 | Supreme Islamic Council of Iraq | (Al-Hikma) Movement - Hakim |

| 2018 | Dawa Party | Nassar - Abbadi |

Besides them, many other minor divisions reflected the high internal Shiite political competition. At a time when the positions of Sistani and Khamenei were more substantial than they are now, the internal struggle of the Iraqi Shiites was in the context of changing coalitions and rivalries, except for some limited violence examples in 2003. Nonetheless, intra-Shia tensions became more violent after the war against ISIS, particularly after 2018. The October demonstrations of 2019 were suppressed in a bloody manner and caused 319 deaths; around 15 thousand were injured (Tawfeeq, 2019). The rebellion of armed Shiite groups against the government has reached the level of attacks on the Prime Minister's house (CNBC,2021). Repeated attacks on the logistical and military bases of the coalition forces and the Kurdistan Region, as well as clashes between the Sadrist movement and Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq in Maysan and Basra, as a severe political and security issue in Iraq, took place. The clashes between Sadr's supporters and the coordination framework in 2022 resulted in 22 deaths (Mansour, 2022).

Conclusion

In general, the nature of the conflict between Shiite forces has two dimensions: religious and material. On the one hand, they are competing for the dominance of religious opinions and authority. Shia elites strive for religious and material gains, and religious authority plays an active role. The change in the Iraqi political system in 2003 and the emergence of a new system provided the Shiites with an opportunity to emerge as the most influential political force in Iraq based on their large population. The prominent Shiite political actors in Iraq have an Islamic background. Except for the October movement, which can be described as a new civil movement, others are directly influenced by religious authority. Moreover, religious authority means the ability to direct the strategic changes of the country, so changes in the position of spiritual authority, especially the roles of Ali al-Sistani and Ali Khamenei, can direct the type of conflict between these forces. One is a Marja who has managed Iraqi politics as a non-state actor for the past few decades, and the other is a religious state actor seeking to increase its influence in Iraq.

The religious-political power of Ali al-Sistani and Ali Khamenei in recent years has decreased. Due to the increasing internal competition, the age factor, a possible power transition in the Shia religious authority, and the geopolitical competition over Iraq, their power level decreased. Lastly, it can be said that the weakness of the power of Shia religious leaders, especially Sistani and Khamanei, has significantly affected the tensions between Shias in Iraq.

Reference

Davison, John, and Haider Kadhim. "Deadly Clashes Rage in Baghdad in Shi'ite Power Struggle." Reuters, August 29 2022, www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iraqi-cleric-Sadr-announces-full-withdrawal-political-life-twitter-2022-08-29. (accessed December 15 2022).

Aawsat. Aawsat, 14 Apr. 2003, http://archive.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8800&article=165482. (accessed 15 Dec 2022).

Reuters (OCTOBER 25, 2019). "Iraq's top Shi'ite cleric Sistani calls for protests to remain peaceful", U.S., available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/iraq-protests-sistani-idUSL2N27A08N (accessed January 3 2023).

Al Arabiya English, (October 10, 2019) "Iraq's Sistani: 'Undisciplined elements' shot protestors, demands govt inquiry" .available at: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2019/10/11/Iraq-s-al-Sistani-Undisciplined-elements-shot-protestors-demands-govt-inquiry (accessed January 3 2023).

Carboni, A. (2020), "Essays on Political Elites and Violence in Changing Political Orders of Middle East and Africa", March, available at: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/42790 (accessed January 3 2023).

Perthes, V., ed. (2004). Arab Elites: Negotiating the Politics of Change. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Volker+Perthes+(ed.).+Arab+Elites%3a+Negotiating+the+Politics+of+Change.-a0150966343

. (accessed December 5 2022).

Thomas, S. (2005) The Global Transformations of Religion and the Transformation of International Relations: The Struggle for the Soul of the Twenty-First Century, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/bfm:978-1-4039-7399-3/1.pdf

. (accessed December 5 2022).

Benjamin Isakhan & Peter E. Mulherin (2018): Shi'i division over the Iraqi state: Decentralization and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies,

DOI: 10.1080/13530194.2018.1500268

Rudaw. (2.05.2021). https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/02052021", available at: https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/02052021 (accessed January 1 2023).

Rudaw. (12.10.2021).https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/121020212, available at: https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/121020212 (accessed January 3 2023).

Al-Aloosy, Massaab. "Sadr versus Khazali: Personal Rivalries and Rising Intra-Shia Tensions in Iraq." EPC. Ae, November 25 November 25 2022, https://www.epc.ae/en/details/featured/sadr-versus-khazali-personal-rivalries-and-rising-intra-shia-tensions-in-iraq-.

Al-Qarawee, Harith Hasan. "The 'Formal' Marjaʿ: Shiʿi Clerical Authority and the State in Post-2003 Iraq." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 46, no. 3, 2018, pp. 481–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2018.1429988.

“Ali Khamenei.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ali-Khamenei.

De Juan, Alexander(2014). "The Role of Intra-Religious Conflicts in Intrastate Wars." Terrorism and Political Violence, vol. 27, no. 4, 2014, pp. 762–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2013.856781.

Nancy T. Ammerman, (2003) "Religious Identities and Religious Institutions," in Michele Dillon, ed., Handbook of Sociology of Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,2003), 207–224.

(accessed December 5 2022).

Michael, Knights and Hamdi, M. (2020), "Hashd Reforms in Iraq Conceal More Than They Reveal", The Washington Institute, June 9, available at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/hashd-reforms-iraq-conceal-more-they-reveal

(accessed January 3 2023).

Farda, Radio(2019). "In Rare Move, Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Sistani Receives Rouhani." RFE/RL, Iran News By Radio Farda, March 14, 2019, https://en.radiofarda.com/a/in-rare-move-iraq-s-grand-ayatollah-sistani-receives-rouhani/29821378.html

(accessed December 5 2022).

Iraqinews(2009). Rafsanjani Describes Meeting with Sistani as "Historic" - Iraqi News. https://www.iraqinews.com/baghdad-politics/rafsanjani-describes-meeting-with-sistani-as-historic/

Hashem, Ali. (2022) "Analysis: Why Is Muqtada Al-Sadr Withdrawing from Iraqi Politics?" Politics News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, August 31 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/30/is-sadrs-announcement-to-retire-from-politics-a-tactic.

Haynes, Jeffrey. "Chapter 1: Religion in International Relations: Theory and Practice." Elgar Online: The Online Content Platform for Edward Elgar Publishing, Edward Elgar Publishing, July 16 2021, https://www.elgaronline.com/display/edcoll/9781839100239/9781839100239.00007.xml.

Isakhan, Benjamin, and Peter E. Mulherin. "Shi'i Division over the Iraqi State: Decentralization and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 47, no. 3, 2018, pp. 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2018.1500268.

Kadhum, Oula. "The Transnational Politics of Iraq's Shia Diaspora." Carnegie Middle East Center, https://carnegie-mec.org/2018/03/01/transnational-politics-of-iraq-s-shia-diaspora-pub-75675.

Kalantari, Mohammad R.(2019) "The Shi'i Clergy and Perceived Opportunity Structures: Political Activism in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon." Taylor & Francis, April 21, 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13530194.2019.1605879?journalCode=cbjm20.

Khalaji, M. (2016), "The Shiite Clergy Post-Khamenei: Balancing Authority and Autonomy", The Shiite Clergy Post-Khamenei: Balancing Authority and Autonomy, October 11, available at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/shiite-clergy-post-khamenei-balancing-authority-and-autonomy

(accessed January 3 2023).

Mamouri, Ali, and Mehdi Khalaji. "Shia Leadership after Sistani Sudden Succession Essay Series." The Washington Institute, September 10 September 2019, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/shia-leadership-after-sistani-sudden-succession-essay-series.

Mamouri, Ali. (2019) "Iraq Meeting between Lebanon's Berri, Sistani Boosts Moderate Shiism in Region." Al, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2019/04/iraq-saudi-iran-sistani-lebanon-nabih-berri.html

Shafaq. "Coordination Framework Asks al-Sistani to Solve Its Conflict With the Sadrist Movement." Coordination Framework Asks al-Sistani to Solve Its Conflict With the Sadrist Movement, January 30 2022, shafaq.com/en/Iraq-News/Coordination-Framework-asks-al-Sistani-to-solve-its-conflict-with-the-Sadrist-movement. (accessed January 3 2023).

Rojhelati, Ziryan. (2022).” The Demonstrations for Mahsa Amini: A Turning Point in Iran, 7 Oct. 2022, www.washingtoninstitute.org/experts/ziryan-rojhelati. (accessed 3 January 2023).

BBC. 2019. "Iraq Unrest: Protesters Set Fire to Iranian Consulate in Najaf." BBC News, November 28 2019, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50580940. (accessed January 3 2023).

INA.2022. "Iraq Starts Paying Iran the Gas Debts." Iraqi News Agency, ina.iq/eng/20109-Iraq-starts-paying-Iran-the-gas-debts.html. Accessed January 3 2023.

Rojhelati, Ziryan. "Powerful Comeback From Sadr." rudawrc.net, August 30 2022, rudawrc.net/en/article/powerful-comeback-from-Sadr-2022-08-30.Accessed January 3 2023.

Wang, H., Nye, J.S. (2022). Power Shifts in the Twenty-First Century. In: Wang, H., Miao, L. (eds) Understanding Globalization, Global Gaps, and Power Shifts in the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3846-7_8 (accessed December 5 2022).

Encyclopedia Britannica, December 16 2022, "Ali Khamenei | Biography, Title, History, and Facts." www.britannica.com/biography/Ali-Khamenei. Accessed January 3 2023.

Biography, "The Official Website of the Office of His Eminence Al-Sayyid Ali Al-Husseini Al-Sistani." Biography, https://www.sistani.org/english/data/2/. (Accessed, January 3 2023.)

Kjetil Selvik & Iman Amirteimour (2020) The Big Man Muqtada al-Sadr: Leading the Street in Iraq under Limited Statehood, Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 5:3-6, 242-259, DOI: 10.1080/23802014.2021.1956367

Rudaw.net, 12 Oct. 2021, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/121020212.

State Department. 2019 Report on International Religious Freedom - United States ... https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-report-on-international-religious-freedom/.

Svensson, Isak. "Fighting with Faith." Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 51, no. 6, 2007, pp. 930–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707306812.

Tawfeeq, Mohammed. "Iraq Protests Death Toll Rises to 319 with Nearly 15,000 Injured." CNN, Cable News Network, November 10 November 10 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/11/09/middleeast/iraq-protest-death-toll-intl/index.html.

Veen, Erwin van, et al. A House Divided. https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2017/a_house_divided/.

"CNBC." CNBC, November 7 2021, www.cnbc.com/2021/11/07/iraqi-pm-chairs-security-meeting-after-drone-attack-on-residence.html.

Yitzhak Nakash, ‘The Shi’ites and the Future of Iraq’, Foreign Affairs 82, no. 4 (2003):17–26.

Graham E. Fuller and Rend R. Francke, ‘Is Shi’ism Radical?’, Middle East Quarterly (March 2000): 11–20, http://www.meforum.org/35/is-Shi’ism-radical (accessed Jan 18, 2012);