A Decade of the Salary Crisis Between Iraq and the Kurdistan Region: Unveiling the Other Side of the Numbers

09-06-2025

Overview

In late May 2025, the Ministry of Finance of the Federal Government of Iraq announced via an official letter that the Kurdistan Region’s total expenditures, including salaries, had been fully covered for the year—despite having only funded four months. The Ministry’s conclusion was based on adding and subtracting three years’ worth of the Kurdistan Region's budget share, as well as calculating Iraq’s total debt from 2015 to the present, treating it as a numerical exercise aimed at justifying a budget cut.

However, the crisis does not end with that letter from the Ministry of Finance or the subsequent clarification issued by the Kurdistan Region’s Ministry of Finance. This issue has persisted for ten years, and to truly understand it, we must revisit the root of the problem and examine the numbers.

For instance, over the past decade, the Kurdistan Region’s education sector has functioned largely through non-contract and, more recently, contract teachers. Its health sector has relied on unpaid volunteers without even daily compensation. Meanwhile, during that same period, Iraq’s education sector appointed more than 319,000 teachers and staff between 2013 and 2023. In the health sector, over 261,000 new doctors and employees were hired—amounting to more than half a million new public servants.

Furthermore, over the past ten years, the total number of new civil servants appointed by the federal government of Iraq exceeded one million. In contrast, the number of civil servants in the Kurdistan Region actually declined by nearly 20,000.

Now that Eid al-Adha has passed, the salaries of public employees in the Kurdistan Region for the month of May remain unpaid, while retirees in federal Iraq have already received their June payments. The total amount allocated to the Kurdistan Region over the past four months of this year—according to a letter from the Ministry of Finance, which outlined the entire budget for 2025—is nearly half of what was spent on the Popular Mobilization Forces (Hashd al-Shaabi) during the same period.

This crisis has once again deepened, and the rhetoric between Erbil and Baghdad has escalated into mutual accusations. These tensions will inevitably have consequences, both immediate and long-term—whether through the repetition of temporary solutions or the emergence of a new approach. However, a decision from the Federal Court alone cannot resolve this persistent crisis between Erbil and Baghdad, nor can the fate of these financial disputes be postponed until after the Iraqi parliamentary elections in November 2025. Instead, all financial issues must be addressed transparently, based on the numbers and data from Iraq’s Ministry of Finance. In this report, we present both the relevant figures and two fundamental options for resolving this ongoing dispute.

Differentiation of Public Sector Labor Force and Expenditures between Iraq and the Kurdistan Region

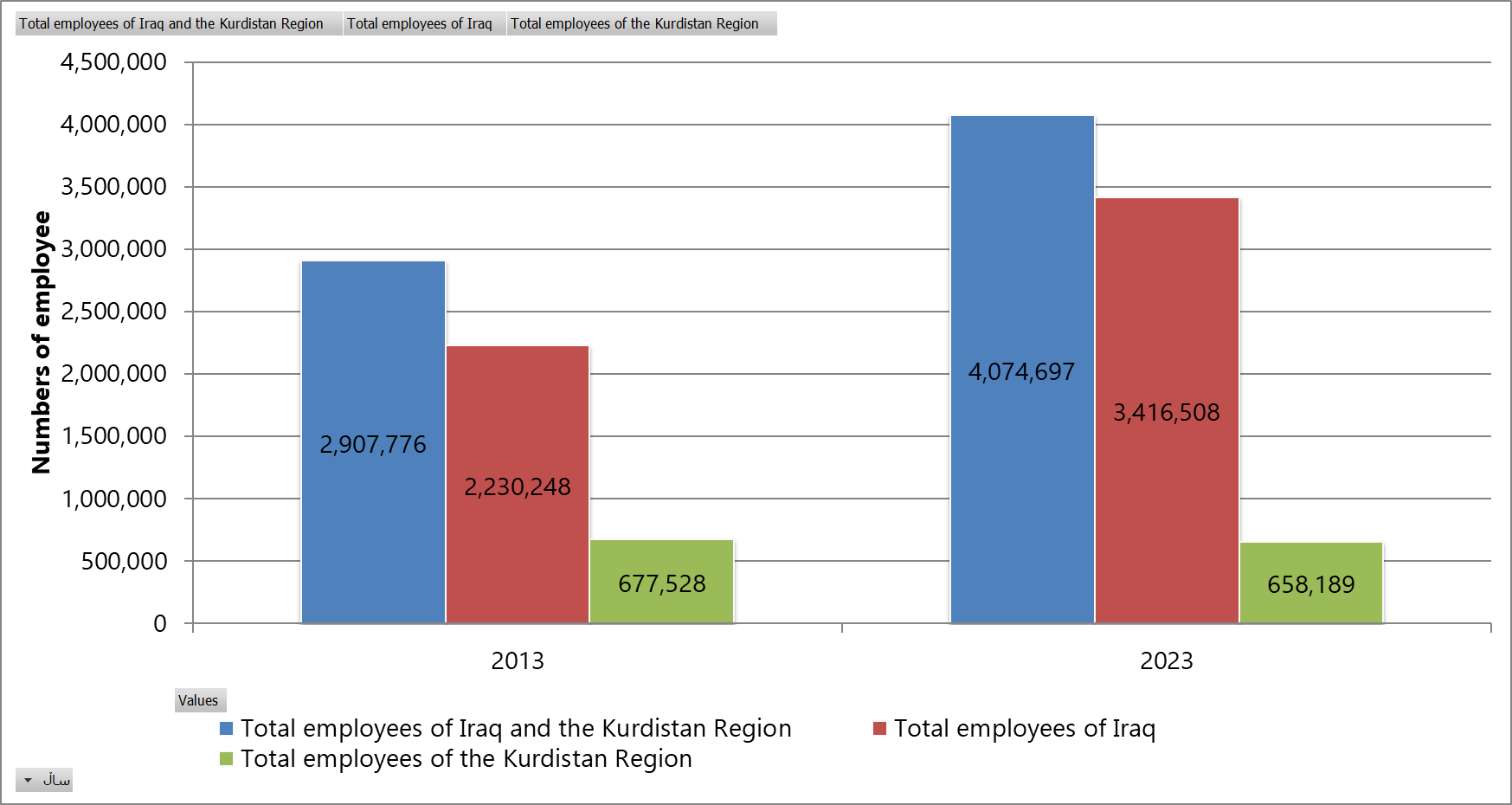

According to Iraq's approved budget law in 2013, the total number of public sector employees across all institutions in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region was 2,907,776. Of this total, 677,528 were employees of the Kurdistan Region. In percentage terms, the Kurdistan Region accounted for 23% of Iraq’s public sector workforce.

After ten years, the three-year budget law for 2023–2025 indicates that the total number of public sector employees in Iraq, including the Kurdistan Region, has risen to 4,074,697. However, the number of employees in the Kurdistan Region has decreased to 658,189. As a percentage, this represents a 7% decline, with the Kurdistan Region's share dropping to 16.15% of Iraq’s total public sector workforce.

Additionally, over the past decade, 1,182,260 new employees have been appointed to federal institutions and governorates in Iraq. In contrast, the Kurdistan Region has seen a reduction of 19,339 public sector employees during the same period.

Graphic 01: A Decade of Public Labor Force Differences in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region

Source: Iraq's Approved Budget 2013, page 40, and Iraq's Approved Budget 2023-2025, page 65

If we take two public service sectors—health and education—in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region as examples, the differences become even more apparent. In the Kurdistan Region, medical college graduates are not appointed, and their scientific training to become doctors is delayed. The health sector operates through a system of “continuous committed volunteering,” with the number of volunteers reaching 11,000 individuals. In contrast, Iraq’s health sector employed 227,166 individuals—including doctors—in 2013. By 2023, this number had increased to 488,550, meaning 261,384 new employees and doctors were appointed, none of whom have ever missed a salary payment.

Over the span of a decade, the number of individuals working as non-contract teachers in the Kurdistan Region’s education sector reached 37,930. These teachers were officially made contractors in 2024, with salaries now ranging between 400,000 to 500,000 Iraqi dinars—paid from the Kurdistan Region’s internal revenue. By contrast, the education sector in Iraq employed 614,613 individuals in 2013. By 2023, the total number of teachers and employees in Iraq’s education sector—excluding the Kurdistan Region—had reached 963,949, indicating that 319,336 new staff were appointed during that period. Perhaps the only notable difference between the two regions' education sectors is the language of instruction: Kurdish in the Kurdistan Region, and Arabic in the central and southern provinces of Iraq.

In terms of security, in 2013 the total number of employees in Iraq's Ministry of Interior was 661,914. By 2023, this number had risen to 701,446. Similarly, the Ministry of Defense had 322,297 employees in 2013, which increased to 453,951 by 2023. This means that 171,186 new employees were appointed in these two sectors over the decade.

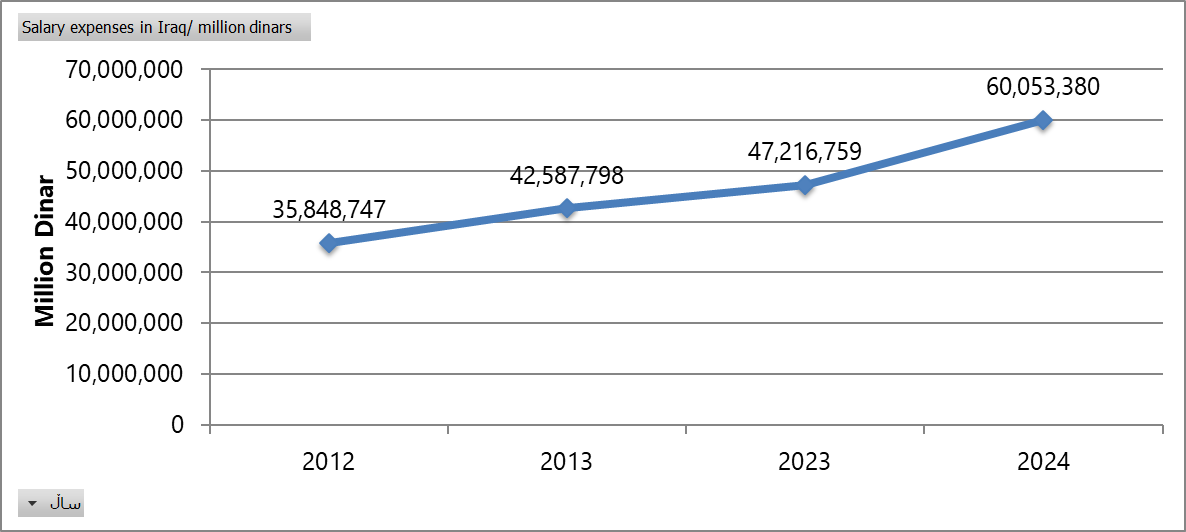

More generally, regarding employee salaries across Iraq, including the Kurdistan Region, the total salary expenditure in 2013 was 42 trillion 587 billion 798 million dinars. However, by 2023, the total salary payments for Iraq’s employees—excluding a single dinar for the Kurdistan Region—reached 47 trillion 216 billion 759 million dinars. This indicates an increase of 4 trillion 626 billion 961 million dinars in salaries, without accounting for Kurdistan Region employees that year.

Furthermore, it is predicted that in the coming years, Iraq’s revenue will be just enough to cover salary expenses. According to data from the Ministry of Finance, in 2012 the total salary expenditure for Iraq and the Kurdistan Region was 35 trillion 848 billion 747 million dinars. By 2024, that number had reached 60 trillion 53 billion 380 million dinars, even though the number of employees in the Kurdistan Region had decreased and they did not receive their 2024 salaries.

This raises a critical question: what can compensate for the 24 trillion 204 billion 633 million dinar increase in salary expenses alone? How should the Kurdistan Region respond to these figures? Should it prepare detailed salary lists, navigate through the various stages of processing, and then wait for review and approval by Iraq’s Minister of Finance and the Prime Minister, in coordination with the governing framework? Or is there an alternative course of action?

Graphic 02: Salary Expenses in Iraq in the Years 2012, 2013, 2023, and 2024

Source: Final Report on Iraq Government Revenues and Expenditures, Ministry of Finance, 08-06-2025

Strategic Options Available to the Kurdistan Region for Resolving the Decade-Long Salary Crisis with Baghdad

Over the past decade, the Kurdistan Region has experienced three distinct phases in managing public sector salary expenses in coordination with Baghdad. The first phase was marked by delays, the second by salary cuts and self-adjustments, and the third by negotiated agreements with the federal government. To fully grasp the impact of each phase, one must ask a public sector salary recipient in the Kurdistan Region about their living conditions—be it a retired teacher, a gardener from the Ministry of Municipalities, or an employee from the Ministry of Agriculture with no other source of income outside the public sector. Only then can one understand how they survived and managed to meet the needs of their children.

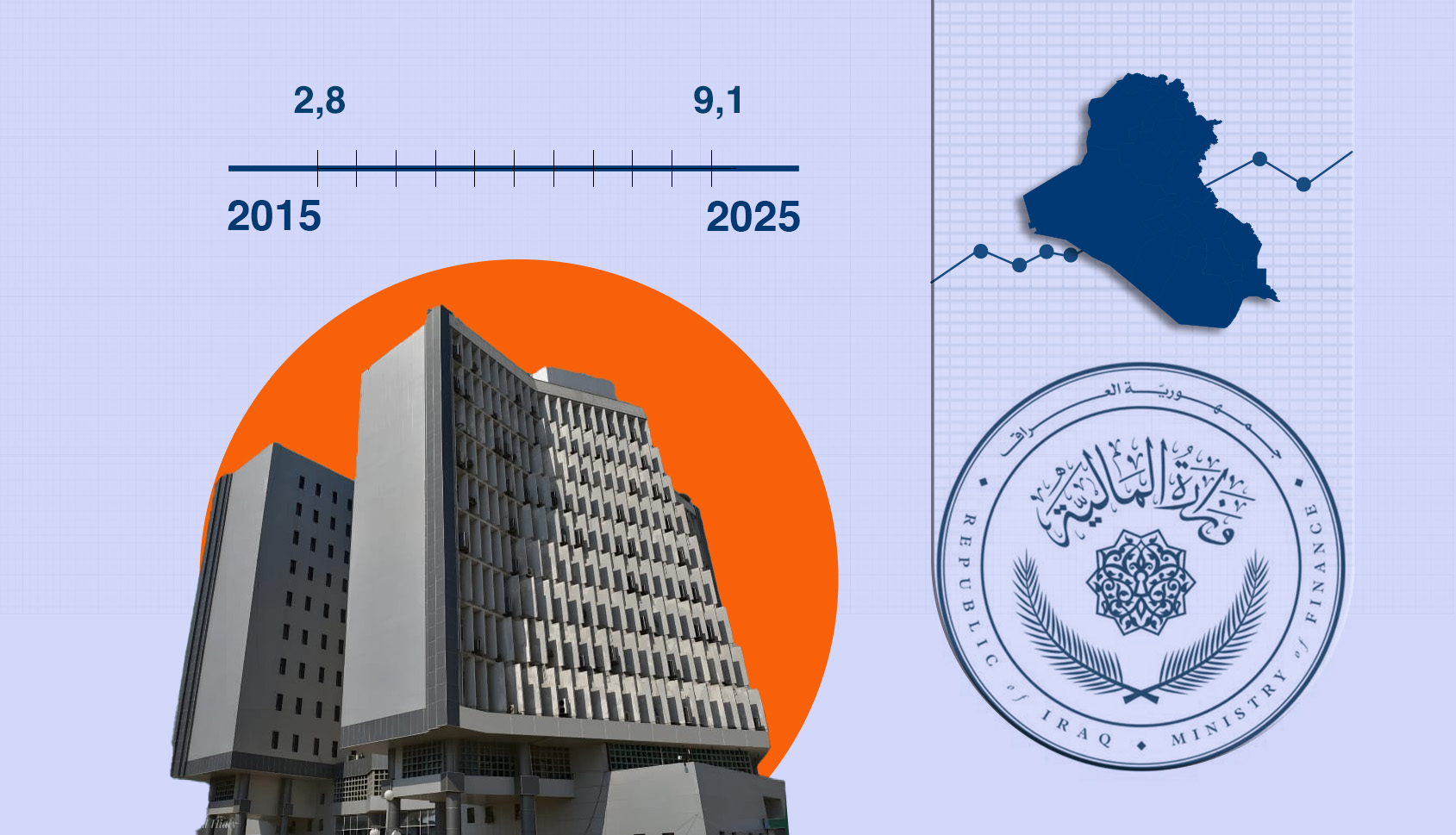

Furthermore, according to the latest statement from Iraq's Ministry of Finance, the Kurdistan Region’s entire salary and employee expenditure allocation for 2025 was exhausted within the first four months of the year. Based on the three-year federal budget, the Kurdistan Region's share is 12.67% of Iraq’s total budget. By the end of April 2025, this allocation—which excluded any development and investment expenditures—had reached a total of 3 trillion, 664 billion, and 213 million Iraqi dinars. This figure includes deductions from Iraq’s accumulated debts dating back to 2015, despite the fact that not a single dinar from those debts was actually spent on the Kurdistan Region. Nonetheless, the Region has been held accountable for them in federal accounting.

Meanwhile, according to the latest population census for Iraq and the Kurdistan Region, the total population of the Kurdistan Region stands at 6,370,688. Yet the amount of money allocated to the Region represents only 59% of the total expenditure allocated to the Popular Mobilization Forces (Hashd al-Shaabi), which received 1 trillion, 502 billion, and 559 million dinars by the end of April.

There are now two fundamental options for resolving the salary crisis of employees in the Kurdistan Region. The first is to restructure the public sector, including expenses and revenues within the Kurdistan Region. The second is to engage in comprehensive negotiations with Baghdad, using data from the past two decades and within a defined timeframe, involving the actual decision-makers in Baghdad—not just the government.

If the first option is pursued, the initial step must involve the monthly publication of detailed reports on total revenues and expenditures, ultimately culminating in the annual budget of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

If the second option is chosen, it must involve resolving the oil and gas file, as well as the Kurdistan Region’s share of Iraq’s national budget—both operational and investment components—based on the Kurdistan Region’s prepared budget, within the framework of Iraq’s annual budget.

Conclusion

Iraq and the Kurdistan Region must reconcile not only on economic issues but also prepare themselves for the major crisis of climate change. Otherwise, under the current mode of operation, not only will these problems remain unresolved, but they will also deepen further. In reality, Iraq's Ministry of Finance seeks to fulfill its financial obligations toward the Kurdistan Region at a lower cost, while also controlling its revenue and expenditure sources. On the other hand, the Kurdistan Region expects to receive nearly half of its budget share from Baghdad by transferring only 50 to 80 billion dinars in non-oil revenue—an amount allocated solely for salaries. This approach will not lead to a resolution.

Now, after two decades, it is time to resolve all outstanding issues between Erbil and Baghdad within a clearly defined timeframe. These issues include: the Kurdistan Region’s share of the national budget; the status of areas outside the Region and the implementation of Article 140; the oil and gas file and its related legislation; the establishment of the Federal Council; compensation for victims of the Baath regime in the Kurdistan Region; and clarification of the Iraqi federal constitution’s provisions regarding the powers of the federal government and the autonomous region. Concrete and practical steps must be taken. Otherwise, yet another election and a new political agreement to form a government with the participation of the Kurdistan Region will merely result in another temporary solution—just like the previous agreement that called for the oil and gas law to be passed within the first six months of the current cabinet, an agreement that has not even resulted in a draft law from the federal Ministry of Oil.

In reality, it is incorrect for the federal state to believe that it has fulfilled its obligations by merely minimizing problems with the Kurdistan Region and manipulating expenditures and revenues through additions and deductions—sending only salaries. On the contrary, the Kurdistan Region’s non-oil revenue should not have reached 2.07 trillion dinars[i] in the first six months of 2023 [1], which equates to approximately 345 billion dinars per month, and by April 2025—nearly 50.5 billion dinars.

It is now widely acknowledged—and the figures are available—that if the Kurdistan Region is part of this federal state, then it should also receive its rightful share from the 49 trillion dinars allocated to investment expenditures. The clearest example of this is the investment in oil and gas. Over the past two years, from the 23 trillion dinars allocated to the Ministry of Oil as part of that broader investment budget, Iraq could have taken the initiative—as part of its federal responsibilities or even in the form of a loan—to establish a national oil and gas company for the Kurdistan Region. From that 23 trillion, at least 3 trillion could have been invested in developing the Miran and Topkhana gas fields, producing electricity that Iraq critically needs.

Looking ahead, Iraq faces numerous challenges—be they political, security-related, social, or stemming from the climate crisis, including water scarcity, increased expenditures, and declining revenues. In light of this, efforts should focus more on reaching agreements and rebuilding, rather than on division and exacerbating problems. It is also true that while the Kurdistan Region urgently needs economic restructuring, Iraq needs it ten times more. It is unacceptable for the federal government to immediately cut salaries in the Kurdistan Region when oil revenues decline and then retroactively claim, based on three years of data, that the Region was non-compliant. If that were the case, why were salaries sent for eleven months in 2024 and four months in 2025?

In conclusion, Iraq is entering a period of significant difficulty. If federalism is to remain a viable structure in Iraq, then serious steps must be taken toward reconciliation and problem-solving in a much shorter timeframe. However, if the constitutional foundations that underpin the federal arrangement between Iraq and the Kurdistan Region are no longer valid, then it is incumbent upon the Kurdistan Region to take the initiative and begin resolving its internal issues independently.

[i] [i] Report of the Kurdistan Regional Government Ministry of Finance to the Finance Committee of the Iraqi Parliament and the Iraqi Ministry of Finance entitled"توضیحات وزیر المالیة والاقتصاد في حکومة إقلیم کوردستان-العراق إلى اللجنة المالیة النیابیة فیما یخص الوضع المالي للإقلیم 1-1-2023 بۆ 31-6-2023، لە 18ی تشرینی یەکەمی 2023، بەغداد.